In the secluded expanse of west Wales, the roughly 100 inhabitants of Tipi Valley live by one cardinal rule: shoes must be ceremoniously removed at the entrance to their huts, yurts, or the traditional tipis.

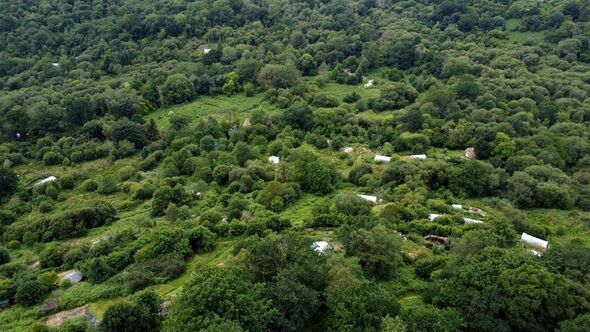

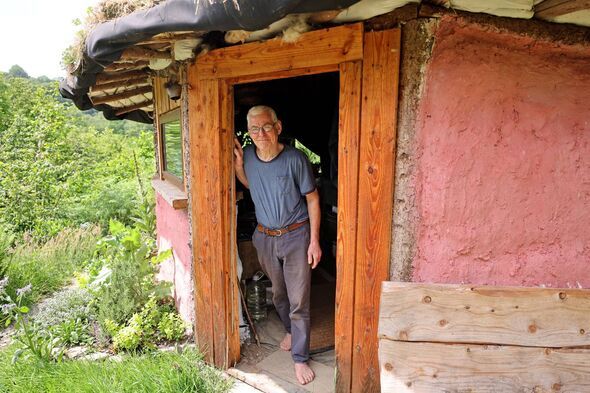

Approaching from the rugged country lane that leads to Cwmdu village in Carmarthenshire, spotting the elusive hamlet celebrated for its unique dwellings, is a challenge. The majority have shifted from tipis to charming turf-roofed huts, which meld into the verdant environment so seamlessly, its easy to barely notice Rik Mayes' abode until its pointed out to you, mere metres away.

Constructing one of these eco-conscientious huts costs about £5,000 and comes with the bonus of being 80% biodegradable. Their efficiency has elevated Tipi Valley to a shining example of sustainable and affordable living.

These huts stand as delightfully whimsical features within the idyllic village resembling a scene plucked from a storybook. The denizens, self-styled as hippies by some, were not always embraced by the neighbouring locales of Cwmdu and Llandeilo.

Delve into Youtube's archives under 'Tipi Valley', and you'll unearth vintage news footage depicting local farmers questioning these hippies claim to the land. In an unsettling recollection, councillor Roland Morgan recounted businesses sporting exclusionary "no hippies" signs in their display windows.

Since 1976, the inhabitants of Tipi Valley have been the landowners, with the bulk of the now 100 acres initially bought for agricultural purposes, sans permission for residential buildings. The crux of the debate over the land's rightful use hinged on whether the nomadic dwellings were legal.

Despite initial concerns about the legality of some structures, Tipi Valley residents breathed a sigh of relief when one of their own, Brig Oubridge, triumphed in a pivotal 2006 court case after a 13-year struggle, establishing his three tents and caravan as lawful. With all huts present in the Valley for over four years without enforcement action, they are now entitled to remain.

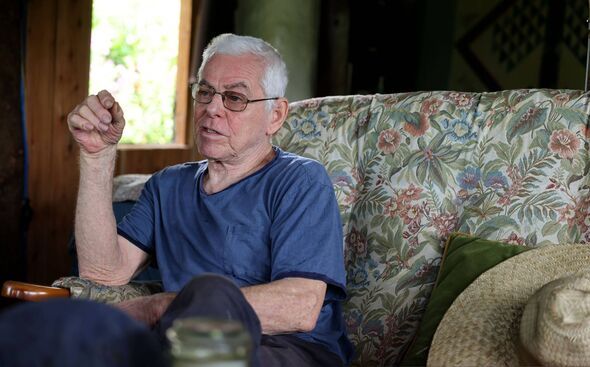

Rik, a reverend from London who has called this place home since 1978, shared with WalesOnline his compact wooden abode. It externally resembles a garden shed but internally is a surprisingly spacious sanctuary featuring a bed, sofa, TV, small kitchen, shower, and office area.

He said: "The council came to terms with us being here many years ago while knowing our ecological mission as such was to live here very simply. They've decided to let us get on with it."

At 77, Rik stands as a pivotal figure in Tipi Valley, perched atop the valley with one of the rare decent mobile signals, inadvertently becoming the unofficial village receptionist. He dismisses any notion of leadership within the community, insisting that there's no such thing.

In Tipi Valley, the concept of hierarchy is non-existent; the hippies residing there believe that the land owns us all. No one forks out rent for their homes, except for one family in a traditional cottage purchased by the community in 1998, and there's no formal vetting for newcomers eager to try out this way of life.

Rik details the ethos of self-assessment for potential residents: "You have to weigh up whether you can cope with the lifestyle and the climate," he says. "That's how Tipi Valley started. We bought the land in 1976 because we wanted people to have the opportunity to come along and give it a go, and that's the way it is."

He highlights the uniqueness of their setup: "We are unique in that sense. There are not many places in the whole of the UK now where that could happen. If you want land in the UK now you're paying a lot of money for it or you're buying a piece of farmland, for example, which is usually far too big."

Rik reflects on the organic growth of their community: "We never started with a vision or a big grand plan. This place was just built by experience. We've just saved as many pennies as we could and we've bought little pieces of land here bit by bit. Now the residents of Tipi Valley have bought 100 acres themselves."

Almost all of the inhabitants live off-grid, with a small number still residing in tipis. Those drawn to Tipi Valley, captivated by an alternative lifestyle and aspiring to become permanent residents, typically stay in the "big lodge" - a large tipi where villagers gather monthly for communal meals and socialising, particularly during the colder months.

The big lodge is situated next to a stream that supplies a well, the primary source of water for the villagers. "People often still turn up and ask to stay here," shares Rik.

"Last week we had a chap staying in the big lodge who approached us so respectfully. He travelled to Swansea, booked a bed and breakfast, then hailed a taxi to bring him here, even having the taxi wait while he sought our permission for future visits.

"I found his manners quite commendable. He visited just to request permission to visit. A few days later, he did return for a proper visit and I believe he's currently residing in the big lodge.

"Another individual in the big lodge arrived yesterday. He mentioned his father used to frequent here when he was younger and he's considering relocating here, so he's exploring the place."

Upon visiting the big lodge WalesOnline reporters we welcomed by Emily Driver from within the communal tipi, which is rather warm. She's presented to extend an invitation to the villagers for her dinner party at her yurt, a brief stroll away.

"I was in the big lodge for four months and I loved it," divulged Emily, 32, who settled there solo last year. "It's quite intense to live in at first. But it's such a grounding space. It slows you down."

Upon her arrival from Leicester, where she lived amid urban bustle, Emily recalled the stark contrast: "I arrived here from Leicester where I lived in the city and as soon as I got here it was a real crash. It was a huge change in speed and it was difficult to get accustomed to at first. I actually found it quite emotional."

Her initial turmoil culminated in a distressed call to family: "I remember ringing my mum crying and she said: 'Emily darling, why don't you sit down and have a cup of tea?' I shouted at her that it was so hard to even make tea in this place. But it's so good because it forces you to be patient."

Before embarking on her journey to Tipi Valley, Emily's life was marked by her grandfather's passing, which led her to reassess her aspirations. She narrated her career pivot: "Before he died grandad said to me: 'Take it whilst you can.' And I decided I wanted to live like this now while I can. I quit my job, quit my flat and came here. I've been here for a year now."

As for her future in this newfound sanctuary, Emily shared her present-focused philosophy: "I don't really think like that. I don't think too much about what is to come. What it is guiding me at the moment are my seeds. My seeds need to be in the ground and watered so I'm here to do that. Once the seeds have grown and I've eaten them, who knows where life will take me?".

"Once people have been here for a while we let them build a permanent dwelling instead of living in a tipi," Rik explains. "He was out of the ordinary because he lived in a tipi for 35 years - far longer than most - before moving into the hut he originally built for his sons to live in while they were at school "so they could turn out smartly".

The Tipi Valley children often attend Talley School, which teaches through the medium of Welsh, endowing many valley youngsters with varying levels of fluency in the language. After his sons' schooldays ended, Rik took over the hut and later felt compelled to move deeper into the valley, nearer to Cwmdu.

He pointed out the nomadic nature of tipis and yurts, highlighting the necessity to relocate them every half-year to fresh areas within the community and He described the craft involved in erecting a tipi: "There is an art to pitching a tipi. It needs to be done in a certain way so when the rain comes the water runs down the tipi and off away from the tipi rather than back towards it.

"In the middle of your tipi you've got your hearth and the hearth gives you heat, light, cooking, everything. You live around that with your family. On the floor around that are rushes and on top of that are sheepskins. Around the edges are your baskets for clothes, wood and toys. You have to travel light in a tipi because you'll be moving on again soon."

Rik povided an intimate glimpse into tipi life, centred around the all-important hearth that brings warmth, illumination, and culinary capabilities. On whether the population of Tipi Valley has fluctuated, Rik responded with levity: "Of course they do," Rik laughed. "If they didn't go we'd have about 4,000 people living here."

His laughter punctuated the reality of a transient lifestyle in this unique community. Living in Tipi Valley is not for the faint-hearted, with many realising they can't endure the harsh winter after romanticising tipi life.

One resident, Peter Francis, had to clear out an astonishing 50 wheelbarrows of belongings left by a short-term dweller who couldn't adapt to life in Tipi Valley. Rik reflected: "Over the years we've had no end of people wanting to live here thinking it's their dream and then during a cold wet winter they've left and left all their stuff and it can be very difficult to sort out."

He explained the minimalist lifestyle required: "It is challenging because it's quite a small space to live in and that means one cannot have many possessions. For example, when I was bringing my children up in a tipi there could only be one toy basket and when it was full one toy had to come out for a new one to go in."

One resident, Peter Francis, had to clear out an astonishing 50 wheelbarrows of belongings left by a short-term dweller who couldn't adapt to life in Tipi Valley. Rik reflected: "Over the years we've had no end of people wanting to live here thinking it's their dream and then during a cold wet winter they've left and left all their stuff and it can be very difficult to sort out."

He explained the minimalist lifestyle required: "It is challenging because it's quite a small space to live in and that means one cannot have many possessions. For example, when I was bringing my children up in a tipi there could only be one toy basket and when it was full one toy had to come out for a new one to go in."

Rik found this simplicity beneficial for his children: "I actually found that very beneficial for my children. They didn't have a lot and I was amazed how unpossessive my kids were. When I was a child I was possessive because I had my bedroom to myself which was like my own little empire."

Reflecting on the unique upbringing his children received, Rik shared: "What I am really pleased about, when I look at my whole life, is that my children were born and bred at Tipi Valley because the opportunity that afforded them was pretty unique - the opportunity to live in the wild and survive with basic means."

Rik was drawn to the valley in 1978 by a mate who suggested they start a school there. "As soon as I came over the hill into the valley I knew I wanted to be here for the rest of my life," he remembered.

"I didn't have any wanderlust to go all over the world or anything like that. I just wanted to find a place I could be freer and where I felt I belonged. I wanted to live close to nature and to bring my family up while living a life I could believe in more than I could believe in the civilisation we've got. Of course, we also need civilisation in part. We couldn't do without the NHS and roads."

Having resided in numerous urban areas including London, Manchester, Bournemouth, and Southend, Rik was 31 when he settled in Tipi Valley. "I find the idea of leaving here now just ludicrous," he declared

"All my life I've just wanted to be around nature and to not have to feel that by crossing some fence I've trespassed into someone else's land. I was brought up on Rupert Bear who lived a wonderful life in the countryside where he could go pretty well wherever he liked. And that's what I wanted."

Peter, who has been a resident since 1983 and is an ex-dairy farmer, has constructed quite a few huts in his time. His latest hut boasts a reciprocal frame roof and an electric induction hob powered solely by solar energy, which is quite the step up from his previous dwellings in Tipi Valley.

A mere stone's throw from his humble abode, the 73 year old tends to a generous allotment, cultivating his own selection of fruits and vegetables, as well as coffee beans. He muses on his minimalist lifestyle, stating: "It's about the philosophy of simplicity - that less is more," though he admits to Rik that this principle doesn't extend to his fondness for ice cream.

Reflecting on his past life just down the road in Taliaris as a dairy farmer, he recounted the financial impracticalities of the trade during the 1980s, exacerbated by the outbreak of mad cow disease. He recalled a troubling conversation with his feed merchant in Llandeilo: "I used to say to my feed merchant 'Where are you getting this stuff from?' And he'd say, 'Quality stuff this is.' But it was actually dead cows I was feeding my cows on.

"No wonder the health problems were rife. It was all going wrong and I couldn't ever work out why. Only in retrospect did it all come out."

After a brief stint in a tipi, which proved challenging, he shared: "I went and spent some time in Africa and came back with the idea of living in a thatched hut instead," revealing that his first self-built hut from local materials tragically burned down due to an unattended lamp."

He sheds light on the evolution of Tipi Valley, explaining: "Nowadays a tipi costs maybe a couple of thousand pounds and with the canvas, under these conditions, you'd be lucky if it lasted three years. They're not very efficient."

Living in a tipi during the summer months can be an enchanting experience, with the warmth of a central fire and the intimacy of nature just outside. However he explained: "So although in the summer it's a wonderful experience to live in a tipi with the focus of the fire in the middle and being wonderfully close to being outside in nature, come the winter with the wind blowing through the door and the damp and dark, it can be difficult."

He contrasts this with the practical design of his own hut, noting: "The thing about these huts is the overhang on the roof which means the walls are dry. Yurts don't have that overhang so the walls are damp when it's raining and that means everything gets a bit damp."

Peter reveals the cost-effectiveness of his dwelling, stating, that the hut was very cheap to build - no more than £5,000. He then adds a thought-provoking comment on housing and legislation: "So nobody needs to be homeless," he says. "They just need to change the planning laws."

In the heart of Peter's abode, a singular roundhouse without distinct rooms but with designated areas for daily life, there's a kitchen and a bed amidst an array of plants. He takes pride in the lack of corners, which discourages hoarding, stating: "There are no corners, Peter points out proudly, so as to remove the temptation to have too much 'stuff'."

Notably absent is a television, a deliberate choice by Peter who quips that he hasn't owned once "since he was a boy," expressing that he prefers to look out of the window. Surrounding his hut with windows and doors, Peter has created a space that opens up to nature, resembling a high-end summerhouse that could fetch a hefty sum on Airbnb.

Reflecting on societal perceptions, Peter mused: "It's funny isn't it, when I first came here we were considered a strange sort - beyond the pale. Wider society just didn't get us. And yet now it's become desirable. People say: 'Let's go glamping and stay in a turf-roofed hut and pay a grand a week.'".

Rik commented: "What they didn't know then is that this life is actually normal. It's the urban, modern way of life which isn't normal, and the sooner people start downsizing the better. Otherwise we don't have a future because the way climate change is going at the moment, it isn't looking good at all."

Rik further adds a tongue-in-cheek suggestion: "So what you've got to do is go back to Cardiff, get a tent and go and live in the park."