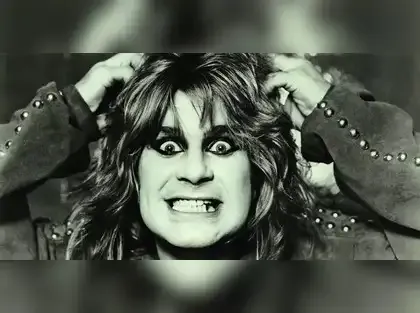

There is Gen Z. And then there's Gen Ozzy. The first is marked by celebration of moderation. The latter is bashless about excess. The signature sound of Gen Z comprises largely of plaintive sighs. As evident in Coldplay songs. Or emotive whinnying noises. Like those in Coldplay songs. The signature sound of Gen Ozzy is loudness, both in amplitude and plenitude.

In a world where 'bingeing' has come to mean the extremely hazardous activity of getting hooked to one episode of an episodic TV show after another, the relatively far more mind-and-body-altering pastime - which the poet Rimbaud so perfectly described in 1871 as 'un long, immense et raisonne dereglement de tous les sens' (a long, immense, and rational disordering of all the senses) - has come to disrepute. By which I mean that being disreputable will no longer bring you repute.

With the body having become a temple, and responsible behaviour - towards fellow humans, other species, and the planet - no longer hippie silliness but mainstream aspiration, like Taylor Swift's music, moderation is today a fetish among 40, 30, even 20-year-olds. The celebration of excess - capsulated in the wonderfully tripping-off-the-tongue phrase, 'sex and drugs and rock'n'roll' - is as enticing for most youngsters today as Black Sabbath's 'Paranoid' is for Narayana Murthy on his off day. Possible, but doubtful.

But like his music - both with Sabbath and in his solo career - Ozzy wasn't really the hormone-dripping, bad boy Bacchus from Birmingham. Even as a teenage burglar who went to prison, young John Osbourne 'thought it would be cool to be a bad guy, so I tried to be a bad guy'. As Ozzy, he was closer to Dennis the Menace, not the American blond kid, but the archetypal badly behaved schoolboy comic strip character in the Scottish comic magazine, The Beano.

Attention-seeking - and attention-getting - remains a Gen Ozzy trait. And in this, the Black Sabbath frontman found his theatrical metier, reaching back to the tradition of the Grand Guignol. Except instead of enacting a style of horror theatre by showcasing graphic and macabre depictions of violence and terror more suitable for a fin de siecle Parisian audience, Ozzy reigned the stage in regalia, the most melodic of banshee vocals, and heavy heaving music marinated in the comedy of comic cons.

Even the 'Prince of Darkness' sobriquet was more 'Halloween satanic' than the genuine darkness of depression and drugs that bands like Joy Division or Alice in Chains were stricken with. But the excess was genuine. Whether it was shocking fat cats by biting the head off a dove in a record company meeting - 'I was so pissed, it just tasted of Cointreau. Well, Cointreau and feathers. And a bit of beak.' - or the infamous 1982 concert in Des Moines, where he chomped off a bat's head, mistaking it to be a rubber toy this time; or when he, inebriated and in desperate 'gotta go' mode, urinated on the Alamo memorial dedicated to American soldiers killed by Mexican troops in 1836 (Ozzy later recounted how a Mexican kid came up to him after the show to say, 'Shit, man... We piss on it every night on our way home')....

What holds Gen Ozzy in awe of Ozzy - and leaves Gen Z disapproving - is not just his ability for such continuous derangement of senses, but also what came out of it: his unmistakable music forged by the riffs of Sabbath guitarist Toni Iommi.

Listen to 'Supernaut' from Black Sabbath's 1972 album Vol. 4, its tip-toe hi-hat intro feeding into that gloriously twisting Iommi riff with Ozzy's searing voice tearing in. It's furious, ecstatic, the sonic equivalent of something spreading very, very quickly through arteries. Or the slow, heavy ogre R&B steps in 'War Pigs' and Ozzy's napalm vocals. Or the Randy Rhoads' guitar in 'Suicide Solution' joined by the python-crush of Ozzy's sneer: 'Wine is fine/ but whisky's quicker./ Suicide is slow with liquor'. Or the sheer melodic blizzard soar of 'Crazy Train'....

Gothic novelist Caroline Lamb once described her lover, the poet Byron as 'mad, bad and dangerous to know'. It's the same reason why Gen Ozzy loves Ozzy. Even if it has to now, grudgingly, metabolically, take to moderation.

In a world where 'bingeing' has come to mean the extremely hazardous activity of getting hooked to one episode of an episodic TV show after another, the relatively far more mind-and-body-altering pastime - which the poet Rimbaud so perfectly described in 1871 as 'un long, immense et raisonne dereglement de tous les sens' (a long, immense, and rational disordering of all the senses) - has come to disrepute. By which I mean that being disreputable will no longer bring you repute.

With the body having become a temple, and responsible behaviour - towards fellow humans, other species, and the planet - no longer hippie silliness but mainstream aspiration, like Taylor Swift's music, moderation is today a fetish among 40, 30, even 20-year-olds. The celebration of excess - capsulated in the wonderfully tripping-off-the-tongue phrase, 'sex and drugs and rock'n'roll' - is as enticing for most youngsters today as Black Sabbath's 'Paranoid' is for Narayana Murthy on his off day. Possible, but doubtful.

But like his music - both with Sabbath and in his solo career - Ozzy wasn't really the hormone-dripping, bad boy Bacchus from Birmingham. Even as a teenage burglar who went to prison, young John Osbourne 'thought it would be cool to be a bad guy, so I tried to be a bad guy'. As Ozzy, he was closer to Dennis the Menace, not the American blond kid, but the archetypal badly behaved schoolboy comic strip character in the Scottish comic magazine, The Beano.

Attention-seeking - and attention-getting - remains a Gen Ozzy trait. And in this, the Black Sabbath frontman found his theatrical metier, reaching back to the tradition of the Grand Guignol. Except instead of enacting a style of horror theatre by showcasing graphic and macabre depictions of violence and terror more suitable for a fin de siecle Parisian audience, Ozzy reigned the stage in regalia, the most melodic of banshee vocals, and heavy heaving music marinated in the comedy of comic cons.

Even the 'Prince of Darkness' sobriquet was more 'Halloween satanic' than the genuine darkness of depression and drugs that bands like Joy Division or Alice in Chains were stricken with. But the excess was genuine. Whether it was shocking fat cats by biting the head off a dove in a record company meeting - 'I was so pissed, it just tasted of Cointreau. Well, Cointreau and feathers. And a bit of beak.' - or the infamous 1982 concert in Des Moines, where he chomped off a bat's head, mistaking it to be a rubber toy this time; or when he, inebriated and in desperate 'gotta go' mode, urinated on the Alamo memorial dedicated to American soldiers killed by Mexican troops in 1836 (Ozzy later recounted how a Mexican kid came up to him after the show to say, 'Shit, man... We piss on it every night on our way home')....

What holds Gen Ozzy in awe of Ozzy - and leaves Gen Z disapproving - is not just his ability for such continuous derangement of senses, but also what came out of it: his unmistakable music forged by the riffs of Sabbath guitarist Toni Iommi.

Listen to 'Supernaut' from Black Sabbath's 1972 album Vol. 4, its tip-toe hi-hat intro feeding into that gloriously twisting Iommi riff with Ozzy's searing voice tearing in. It's furious, ecstatic, the sonic equivalent of something spreading very, very quickly through arteries. Or the slow, heavy ogre R&B steps in 'War Pigs' and Ozzy's napalm vocals. Or the Randy Rhoads' guitar in 'Suicide Solution' joined by the python-crush of Ozzy's sneer: 'Wine is fine/ but whisky's quicker./ Suicide is slow with liquor'. Or the sheer melodic blizzard soar of 'Crazy Train'....

Gothic novelist Caroline Lamb once described her lover, the poet Byron as 'mad, bad and dangerous to know'. It's the same reason why Gen Ozzy loves Ozzy. Even if it has to now, grudgingly, metabolically, take to moderation.

Indrajit Hazra

Editor, Views