Oops, Bollywood did it again - offended people! This time it’s not the usual #boycott brigade frothing over real and perceived slights against history, religion or politics but people from Kerala, India’s most literate state, known for their easy humour and ability to take a joke on themselves.

The OOTD — outrage of the day — revolves around the upcoming cross-cultural romcom Param Sundari, starring Siddharth Malhotra and Jahnvi Kapoor that has managed to rile the generally genial Malayali into making a flood of angry posts and reels calling out the lame portrayal of the community. The tsunami of online chatter is based on a mere trailer where Kapoor’s diction, name, kasavu sari and stock shots of Kalaripayattu and backwaters have come in for intense roasting. The film may or may not be guilty but for now, the videos are relentless, racking up millions of views and reigniting a long-pending debate against Bollywood’s stereotypes.

Meanwhile, Maddock Films, the production house, decided to make matters worse by issuing copyright strikes against creators. Coming as it does on the heels of the National Awards controversy — where The Kerala Story, a film accused of spreading propaganda against the state, was given top honours — the issue has blown up across the internet. Memes featuring Shalini Unnikrishnan, the character played by lead actress Adah Sharma, were already doing the rounds when Kapoor’s Thekeppatt Sundari Damodaran Pillai came about. And then, Malayali anger exploded.

The mess is immense but the discussion is valid: is it yet another case of social-media fuelled rage or is it genuine exasperation from an aware audience unwilling to accept caricature in the name of entertainment? In this case of “Malayali content creators Vs Bollywood”, the scale tilts towards the latter.

So what’s new?

Frankly, nuance has never been a strength of Hindi cinema. This is an industry which has revelled in creating archetypical characters — the happy-go-lucky alcoholic Christian D’souza or D’costa, the skirt-wearing typist who loves to coo “What are you doing man?”, the balle-balle bellowing turbaned Sikh, the liberal Bengali and more. For years, such portrayals have been accepted and even celebrated. Case in point: Chennai Express where Deepika Padukone, playing a Tamilian, spoke an accent that does not exist on this planet. So why are we angry now?

Two simple reasons: Awareness and social media. Dubai-based RJ Pavithra Menon, whose viral video on the topic was among the first to spark the conversation, believes Bollywood was long given the benefit of the doubt because audiences didn't know better. “With awareness and exposure to global content and cultures, we now understand issues like racism, casteism and representation far better and can tell the difference between exaggeration, spoof and actual representation. The point is, we can’t be entertained by shoddy work,” says Menon.

Pertinently, South Indian cinema has been having its moment in the sun post Covid with OTT platforms opening up viewers to new perspectives. Kannada and Telugu blockbusters like KGF and Pushpa reshaped the mass market, while Malayalam and Tamil films won acclaim for originality, forcing cinephiles to open their eyes to the cinematic soft power of the region. Therefore, Bollywood’s inaccurate and simplistic characterisation is even more of an eyesore for a discerning viewer. As Menon says, “Until now Bollywood’s grandeur and money spoke but art speaks louder. The power of vocalising our opinions came because South Indians are making beautiful art and this global recognition has given us the power to speak up when we are wronged.”

Mumbai-based actor-filmmaker Divya Unny, who shared her own powerful video on caricaturish representation of South Indians recalls being often asked to put on an accent during auditions. Bollywood uses a template to represent South Indians, making them superficial with the lack of depth and research becoming woefully evident, she says in her reel. “Show a banana leaf meal, throw in names of some famous stars, a bit of Bharatnatyam or Mohinattam…it’s time to grow up and move away from these stereotypes. Audiences do not want this caricaturish comedy,” observes Unny.

Clearly, the audience has grown up even if filmmakers remain blinkered. Senior journalist Avijit Ghosh, author of Cinema Bhojpuri and When Ardh Satya Met Himmatwala, reminds us that mainstream Hindi cinema was never about accuracy. “Commercial films have always been about maintaining stereotypes rather than breaking them. They are a shorthand through which the larger audience ‘gets’ a character,” he notes.

Screenwriter Althea Kaushal, herself a half-Malayali, agrees. “Bollywood looks for beauty, not realism,” she says. “But here it is necessary to make a distinction between being irritated and getting offended. Is the state or its people getting insulted? I don’t think so. Does Jahnvi’s ‘explanation’ scene (of the difference between the four South Indian states) at the end of the trailer reinforce clichés? Yes. But has the community been wronged? Not really. So it’s not worth the outrage. Honestly, I found Chennai Express’s Lungi dance far more ridiculous.”

A Look at History

While the reaction of Gen Z and millennials to this particular controversy has been far more passionate, a glimpse into Bollywood’s checkered tryst with representation provides some interesting insights. In the ’60s and ’70s, southern studios like Gemini, Prasad Productions and AVM remade blockbusters in Hindi, often hiring advisors to adapt cultural details. “If the Tamil film showed a local tradition, the Hindi version replaced it with a north Indian equivalent,” says Ghosh. But there were also cases like that of the cult classic Padosan (1968), where Mehmood’s “South Indian” antagonist remained largely unchallenged despite drawing flak from critics primarily due to limited avenues for protest.

Then came the phase in the 70s and 80s, when there was a clear demarcation between “parallel” and “commercial” cinema. The former was expected to be realistic and serious while the latter sold fantasy and fluff. “Now people are probably expecting commercial films to be realistic which has resulted in this response,” says Ghosh.

Social Media’s Role

The sheer volume of the conversation is reflective of the larger polarised discourse in the hypersensitive times we live in, feels Ghosh. “Back then people would talk about it with friends or shoot off a letter to the editor. It did not enter the political frame or become major outrage points. These days social media amplifies everything. That said, expressing displeasure through reels and posts is perfectly democratic.”

Social media has indeed increased sensitivity, awareness and wokeness, which in its most extreme form, can lead to cancellation. As Bollywood is probably finding out, when you can’t get the basics right, you will get corrected. And Bollywood is an equal opportunity offender with stereotypes extending beyond the boundaries of India. Pakistani theatre actor Asad Raza Khan laughs at the clichés his community has been subjected to. “In Karachi you won’t find men with soorma starting every line with ‘jee janaab.’ Maybe they should visit Dubai to see how regular Pakistanis dress and talk! However, this tendency exists in Pakistani entertainment as well, in relationship dynamics; be it evil phupis, their useless sons or straying husbands, relationships get caricatured all the time,” he says.

Khan argues that stereotyping is driven by a combination of four elements. Economics, that lead filmmakers to choose saleable stars over competent actors; lack of cultural awareness resulting in misrepresentation; an inclination to sell “mock culture” and zero effort or research. “What they don’t understand is that gag comedy has become very common on social media. Viewers expect more elevated content from films, not the same tired jokes,” he says.

Two Schools of Thought

Hollywood has learnt the lessons well, coming a long way from portraying South Asians as snake charmers or Maharajas to becoming more inclusive. By comparison, Bollywood has a long way to go though mere outrage may not be productive.

Kaushal strongly feels the current anger about representation, while understandable, is pointless because there are more urgent issues that need to be addressed. “We should not be defending borders in a country. If a film is fiction and in the process, elements that a region is most known for gets highlighted, what’s the harm? Secondly, why are Keralities looking for representation from Bollywood? They should be proud of the cinema they are making. The outrage over The Kerala Story is far more valid. A Param Sundari can cause irritation but let’s not be too offended.”

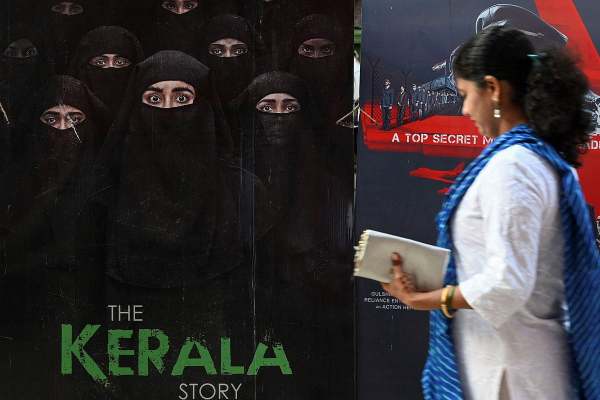

A moviegoer walks past a poster of the film - The Kerala Story - at a movie theatre in Mumbai.

Khan has a different take as he believes it’s time for course correction from the topmost echelons. “Commercial Hollywood or Bollywood may have the lowest bar but the highest reach so what they show on screen can shape the larger psychology of the audience subliminally. The more these things are highlighted the more there will be Bollywood 2.0.”

When Bollywood got it right

2.0 or not but mainstream Hindi films certainly need to read the room. In the past, there have been movies like Shoojit Sircar’s Piku or Anvita Dutt’s Bulbbul or Abhishek Chaubey’s Udta Punjab where stories were set in specific communities yet the writers got the nuances, language and details perfectly right. To make amends, filmmakers can take a few easy steps. For one, stick to facts. Two, let actors go in for localisation training. And then get a cultural advisor when making films about a community. “These measures can avoid bloopers and create a more palatable representation,” says Ghosh.

Hopefully Bollywood is listening, for one thing is certain: in an era where young audiences are vocal, Bollywood’s lowest-bar shortcuts may no longer work. Lazy stereotypes aren’t just annoying anymore — they’re being called out, reel by reel, post by post.

'Param Sundari' trailer backlash: 5 times Bollywood stereotyped South India on screen Param Sundari trailer: UAE creators react as Bollywood stereotypes Keralites yet again