The professor had a faint air of mystery about him.

A bodyguard trailed behind as the academic came and went from his apartment on a tree-lined street in central Tehran, neighbors said. A taciturn man with a tight gray beard, nobody was quite sure why he needed protection. Everyone knew better than to ask.

Little of that concerned Amirali Khorami, the teenager who lived next door. Obsessed with video games and soccer, Amirali, 14, dreamed of becoming a professional goalkeeper, his family said. He hardly noticed the elderly neighbor who sometimes exchanged pleasantries with his father on the street.

Then, on June 13, in the early hours of the 12-day war between Israel and Iran that later drew in the United States, their fates were inextricably joined. An Israeli bomb crashed into the home of the professor, Dr. Ahmadreza Zolfaghari, who, it turned out, was one of Iran's leading nuclear scientists.

Not only did the blast kill the scientist and his family, it also tore into surrounding buildings, smashing through wall after wall until it reached the cramped bedroom where Amirali was sleeping and killed him too.

Rescuers took an hour to pull Amirali's crushed body from the debris, his 21-year-old brother, Amirmohammad, told me as he stood in the wreckage of their bedroom, nearly two months after the strike.

Granted rare journalist visas, we were in Iran for eight days to gauge the aftermath of the country's most devastating war in decades. Although the government supplied our translator, whose work we verified, and fear of the authorities is pervasive, many people spoke with surprising candor.

Amirmohammad pointed to a dust-smeared Spider-Man figure poking from the rubble. "Amirali loved life," he said. "What did he do to deserve death?"

Hundreds of civilians died in June, when Israeli bombs and missiles rained down for 12 days across Tehran, a sprawling city of 10 million people, leaving it bloodied and reeling. American bombers pounded key nuclear facilities to the south. But it was the strikes on the capital that registered the deepest shock among many Iranians, signaling that their country's old rivalry with Israel had entered a volatile and dangerous new phase.

Israel sought to cripple Iran's nuclear program and weaken its leadership in the region at a pivotal moment, when Iranian proxies like Hamas and Hezbollah had been badly weakened. Fighter jets and drones pounded military command centers and other targets, wiping out Iran's top military command as well as at least 13 nuclear scientists.

But the bombs also struck a crowded prison, a TV station broadcasting the news, and apartments filled with sleeping families. Even commuters were not safe: bombs that fell on rush-hour traffic tossed vehicles into the air like toys, video footage showed.

In all, 700 civilians and nearly 400 military and nuclear personnel died, according to Iran's Health Ministry. The Human Rights Activists News Agency, an independent U.S.-based group, confirmed 436 civilian deaths, 435 military deaths, and 319 yet unaccounted for.

Iranian counter-strikes on Israel, including ballistic missiles that struck major cities, killed 31 people, according to Israel's Foreign Ministry.

Tehran last suffered a major assault in 1988, when Iraqi Scud missiles slammed into crowded neighborhoods and killed at least 400 civilians. But those barrages were less intense than this latest war, many residents said. And there was little faith that a shaky ceasefire, agreed to by Iran and Israel on June 25, will hold for long.

"We're keeping our eyes to the skies," Fereydoon Soltani, a stone cutter, told me as he left a memorial service for Gen. Hossein Salami, the assassinated commander of Iran's powerful Revolutionary Guard. "Nobody believes this is over."

A New Way of War

The short yet fierce war signaled a seismic shift to an enmity that has shaped the modern Middle East.

For years, Israel and Iran were engaged in a shadow war. Iran fought Israel through its various regional proxies. Israel tried to cripple Iran's nuclear program through sabotage, subterfuge and targeted killings. On the streets of Tehran, assassins on motorbikes stuck bombs to the cars of nuclear scientists or shot them in their seats. Wives and children were left largely unharmed.

In June, Israel cast aside that doctrine in favor of blunt military action that killed hundreds of civilians. Some strikes killed residents with the bad luck to live beside a nuclear scientist or a senior general; others were aimed squarely at civilian targets with the apparent aim of destabilizing Iran's government.

The deadliest episode, an hourlong bombardment of the notorious Evin prison, killed 80 people including prisoners, social workers and children, according to Iran's health ministry. Israeli officials justified the attack as a blow against "oppression." Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International called it a likely war crime.

Iran's autocratic leaders have tried to put a brave face on their losses, seeking to channel national grief into their brand of defiant nationalism. "What doesn't kill you makes you stronger," Ebrahim Rezaei, the spokesperson for the parliament's national security committee, said in an interview.

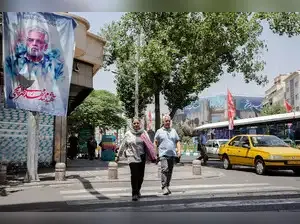

Giant portraits of slain generals and nuclear scientists stared down over Tehran's main squares. At official commemorations, video screens showed missiles streaking toward Israel. A digital countdown to "the elimination of Israel" -- at 5,533 days the day I visited -- glows defiantly in the city's Palestine Square.

At the University of Tehran, students packed into a hall where a turbaned cleric representing Iran's supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, issued revisionist claims about the recent war. "The U.S. and Israel begged us for a ceasefire," he declared.

Fatemeh Panji, a 24-year-old student, was listening attentively. The war had been a terrifying experience, she said, recounting how she had hunkered inside her dorm as bombs fell nearby. But it also left her determined to devote her future to Iran, "even my life," she told me.

Others were more ambivalent, balancing anger toward Israel with frustration at their own government. Already, severe American sanctions intended to pressure Iran over its nuclear program have crippled the country's economy, while fury toward the country's clerical rulers led to huge street protests, most recently in 2022.

This summer, their misery was heightened by chronic water and electricity shortages during the worst heat wave in years. Now, since the war, many no longer feel secure even in their own homes.

When Ahmad Hayatizadeh was thrown from his bed on June 13, he feared it was the major earthquake that geologists have long predicted for Tehran. In fact, it was the bomb targeting Zolfaghari, the nuclear scientist, who lived across the street.

Now Hayatizadeh, a retired businessperson, struggles to sleep through the night. "If I'm not safe here," he said, standing beside a shredded sofa, "then where can I go?"

Complicated Feelings About War and America

One evening in late July, thousands of families crowded into a corner of Behesht-e Zahra, Tehran's vast main cemetery, to remember those killed 40 days earlier, an important milestone for Iranian Shiites.

Iran's history has played out here before. During the 1979 revolution, Iran's first supreme leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, rushed to this cemetery upon his return from exile to deliver a speech that laid bare his ambitions for the country.

Now, Behesht-e-Zahra was an illustration of where his confrontational approach had taken Iran. Hundreds of newly dug graves, scattered with rose petals, lined a section reserved for those killed in the June war. Black-clad women leaned over marble tombstones, murmuring prayers. Men quietly beat their chests, blinking back tears.

A young man with a soulful voice intoned tributes into a microphone, surrounded by mourners holding aloft photos of the dead -- army officers and soldiers, but also businesspeople, students and Red Crescent volunteers. The youngest victim was 2 months old: Rayan Ghasemian, an infant boy buried with his mother.

For a few brief hours, the ceremony brought together Iranians at the heart of a brutal security apparatus with citizens who had nothing to do with it. Rage-tinted grief united them.

"They think they can weaken us by killing our commanders," said Leila Alizadeh, clutching a photo of her brother, an air force officer who she said was killed near the underground uranium enrichment facility in Fordo. "But it will only make us stronger."

Hadis Pazouki, an ashen-faced fashion executive, leaned over the grave of her father, killed in the street by one of the bombs that hit Evin Prison. "He never attended a political rally in his life," she told me, her eyes flashing. "What did he do to Israel or America?"

The war had stirred up complicated feelings, Pazouki added. "Young Iranians admire the American dream," she said. But blame for her father's death lay squarely with President Donald Trump, she said, for pulling out of the nuclear deal with Iran in 2018: "This war is on him."

Another mourner, who gave her name as Khadijeh, sidled up. Like many Iranians we interviewed, she was reluctant to give her full name out of fear of retribution from the authorities. "You should know that Iranians are not the same as their government," she said.

Her daughter, standing beside her, offered a few phrases in German, a language she had started to learn in the hope of emigrating.

"No sane mother will let her children stay in this country at war," Khadijeh said. What Iranians wanted more than anything, she added, was "peace and freedom."

An Acute Sense of Vulnerability

The hopes of some Israeli leaders that the war would spark a popular revolt proved wildly misplaced.

Instead of rising against their leaders, Iranians have limped back to a semblance of normality. Those who fled during the fighting have mostly returned. Upscale restaurants in the posher districts of northern Tehran are again packed on weekends. The city's notorious traffic jams have resumed.

At the same time, an acute sense of vulnerability courses through the city. The collapse of Iran's air defense systems, which left the country undefended during 12 days of Israeli strikes, quietly worries many residents. Official reassurances are belied by an intensive hunt for traitors that has led to the execution of 10 accused spies since June.

Yet there is also a sense of flux, that the war changed something intangible in Iran, and might push the country in an unpredictable new direction.

"Anything seems possible now," Newsha, a 17-year-old student, said with a laugh outside a bustling pizza joint in a fashionable corner of central Tehran, standing beside a cousin who was visiting from Shiraz.

The young women, who asked to be identified by one name, didn't want to talk politics. But in the next breath, they said they yearned for change. Some was already underway. Like growing numbers of women in Tehran, they did not wear the mandatory hijab -- a dress code the government has relaxed, at least for now.

For others, though, this is a moment to double down on belligerence. Members of the Student Basij, a volunteer group affiliated with the Revolutionary Guard, clustered the ruins of Zolfaghari's home.

The women painted tulips, Iran's national flower, on lamp posts, while the men draped flags on the rubble and called for revenge. "We want war," said Ali Soleymani, a law student.

Beside him, new graffiti gleamed from a chunk of broken concrete. "You started it," read the slogan. "We will finish it."

A bodyguard trailed behind as the academic came and went from his apartment on a tree-lined street in central Tehran, neighbors said. A taciturn man with a tight gray beard, nobody was quite sure why he needed protection. Everyone knew better than to ask.

Little of that concerned Amirali Khorami, the teenager who lived next door. Obsessed with video games and soccer, Amirali, 14, dreamed of becoming a professional goalkeeper, his family said. He hardly noticed the elderly neighbor who sometimes exchanged pleasantries with his father on the street.

Then, on June 13, in the early hours of the 12-day war between Israel and Iran that later drew in the United States, their fates were inextricably joined. An Israeli bomb crashed into the home of the professor, Dr. Ahmadreza Zolfaghari, who, it turned out, was one of Iran's leading nuclear scientists.

Not only did the blast kill the scientist and his family, it also tore into surrounding buildings, smashing through wall after wall until it reached the cramped bedroom where Amirali was sleeping and killed him too.

Rescuers took an hour to pull Amirali's crushed body from the debris, his 21-year-old brother, Amirmohammad, told me as he stood in the wreckage of their bedroom, nearly two months after the strike.

Granted rare journalist visas, we were in Iran for eight days to gauge the aftermath of the country's most devastating war in decades. Although the government supplied our translator, whose work we verified, and fear of the authorities is pervasive, many people spoke with surprising candor.

Amirmohammad pointed to a dust-smeared Spider-Man figure poking from the rubble. "Amirali loved life," he said. "What did he do to deserve death?"

Hundreds of civilians died in June, when Israeli bombs and missiles rained down for 12 days across Tehran, a sprawling city of 10 million people, leaving it bloodied and reeling. American bombers pounded key nuclear facilities to the south. But it was the strikes on the capital that registered the deepest shock among many Iranians, signaling that their country's old rivalry with Israel had entered a volatile and dangerous new phase.

Israel sought to cripple Iran's nuclear program and weaken its leadership in the region at a pivotal moment, when Iranian proxies like Hamas and Hezbollah had been badly weakened. Fighter jets and drones pounded military command centers and other targets, wiping out Iran's top military command as well as at least 13 nuclear scientists.

But the bombs also struck a crowded prison, a TV station broadcasting the news, and apartments filled with sleeping families. Even commuters were not safe: bombs that fell on rush-hour traffic tossed vehicles into the air like toys, video footage showed.

In all, 700 civilians and nearly 400 military and nuclear personnel died, according to Iran's Health Ministry. The Human Rights Activists News Agency, an independent U.S.-based group, confirmed 436 civilian deaths, 435 military deaths, and 319 yet unaccounted for.

Iranian counter-strikes on Israel, including ballistic missiles that struck major cities, killed 31 people, according to Israel's Foreign Ministry.

Tehran last suffered a major assault in 1988, when Iraqi Scud missiles slammed into crowded neighborhoods and killed at least 400 civilians. But those barrages were less intense than this latest war, many residents said. And there was little faith that a shaky ceasefire, agreed to by Iran and Israel on June 25, will hold for long.

"We're keeping our eyes to the skies," Fereydoon Soltani, a stone cutter, told me as he left a memorial service for Gen. Hossein Salami, the assassinated commander of Iran's powerful Revolutionary Guard. "Nobody believes this is over."

A New Way of War

The short yet fierce war signaled a seismic shift to an enmity that has shaped the modern Middle East.

For years, Israel and Iran were engaged in a shadow war. Iran fought Israel through its various regional proxies. Israel tried to cripple Iran's nuclear program through sabotage, subterfuge and targeted killings. On the streets of Tehran, assassins on motorbikes stuck bombs to the cars of nuclear scientists or shot them in their seats. Wives and children were left largely unharmed.

In June, Israel cast aside that doctrine in favor of blunt military action that killed hundreds of civilians. Some strikes killed residents with the bad luck to live beside a nuclear scientist or a senior general; others were aimed squarely at civilian targets with the apparent aim of destabilizing Iran's government.

The deadliest episode, an hourlong bombardment of the notorious Evin prison, killed 80 people including prisoners, social workers and children, according to Iran's health ministry. Israeli officials justified the attack as a blow against "oppression." Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International called it a likely war crime.

Iran's autocratic leaders have tried to put a brave face on their losses, seeking to channel national grief into their brand of defiant nationalism. "What doesn't kill you makes you stronger," Ebrahim Rezaei, the spokesperson for the parliament's national security committee, said in an interview.

Giant portraits of slain generals and nuclear scientists stared down over Tehran's main squares. At official commemorations, video screens showed missiles streaking toward Israel. A digital countdown to "the elimination of Israel" -- at 5,533 days the day I visited -- glows defiantly in the city's Palestine Square.

At the University of Tehran, students packed into a hall where a turbaned cleric representing Iran's supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, issued revisionist claims about the recent war. "The U.S. and Israel begged us for a ceasefire," he declared.

Fatemeh Panji, a 24-year-old student, was listening attentively. The war had been a terrifying experience, she said, recounting how she had hunkered inside her dorm as bombs fell nearby. But it also left her determined to devote her future to Iran, "even my life," she told me.

Others were more ambivalent, balancing anger toward Israel with frustration at their own government. Already, severe American sanctions intended to pressure Iran over its nuclear program have crippled the country's economy, while fury toward the country's clerical rulers led to huge street protests, most recently in 2022.

This summer, their misery was heightened by chronic water and electricity shortages during the worst heat wave in years. Now, since the war, many no longer feel secure even in their own homes.

When Ahmad Hayatizadeh was thrown from his bed on June 13, he feared it was the major earthquake that geologists have long predicted for Tehran. In fact, it was the bomb targeting Zolfaghari, the nuclear scientist, who lived across the street.

Now Hayatizadeh, a retired businessperson, struggles to sleep through the night. "If I'm not safe here," he said, standing beside a shredded sofa, "then where can I go?"

Complicated Feelings About War and America

One evening in late July, thousands of families crowded into a corner of Behesht-e Zahra, Tehran's vast main cemetery, to remember those killed 40 days earlier, an important milestone for Iranian Shiites.

Iran's history has played out here before. During the 1979 revolution, Iran's first supreme leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, rushed to this cemetery upon his return from exile to deliver a speech that laid bare his ambitions for the country.

Now, Behesht-e-Zahra was an illustration of where his confrontational approach had taken Iran. Hundreds of newly dug graves, scattered with rose petals, lined a section reserved for those killed in the June war. Black-clad women leaned over marble tombstones, murmuring prayers. Men quietly beat their chests, blinking back tears.

A young man with a soulful voice intoned tributes into a microphone, surrounded by mourners holding aloft photos of the dead -- army officers and soldiers, but also businesspeople, students and Red Crescent volunteers. The youngest victim was 2 months old: Rayan Ghasemian, an infant boy buried with his mother.

For a few brief hours, the ceremony brought together Iranians at the heart of a brutal security apparatus with citizens who had nothing to do with it. Rage-tinted grief united them.

"They think they can weaken us by killing our commanders," said Leila Alizadeh, clutching a photo of her brother, an air force officer who she said was killed near the underground uranium enrichment facility in Fordo. "But it will only make us stronger."

Hadis Pazouki, an ashen-faced fashion executive, leaned over the grave of her father, killed in the street by one of the bombs that hit Evin Prison. "He never attended a political rally in his life," she told me, her eyes flashing. "What did he do to Israel or America?"

The war had stirred up complicated feelings, Pazouki added. "Young Iranians admire the American dream," she said. But blame for her father's death lay squarely with President Donald Trump, she said, for pulling out of the nuclear deal with Iran in 2018: "This war is on him."

Another mourner, who gave her name as Khadijeh, sidled up. Like many Iranians we interviewed, she was reluctant to give her full name out of fear of retribution from the authorities. "You should know that Iranians are not the same as their government," she said.

Her daughter, standing beside her, offered a few phrases in German, a language she had started to learn in the hope of emigrating.

"No sane mother will let her children stay in this country at war," Khadijeh said. What Iranians wanted more than anything, she added, was "peace and freedom."

An Acute Sense of Vulnerability

The hopes of some Israeli leaders that the war would spark a popular revolt proved wildly misplaced.

Instead of rising against their leaders, Iranians have limped back to a semblance of normality. Those who fled during the fighting have mostly returned. Upscale restaurants in the posher districts of northern Tehran are again packed on weekends. The city's notorious traffic jams have resumed.

At the same time, an acute sense of vulnerability courses through the city. The collapse of Iran's air defense systems, which left the country undefended during 12 days of Israeli strikes, quietly worries many residents. Official reassurances are belied by an intensive hunt for traitors that has led to the execution of 10 accused spies since June.

Yet there is also a sense of flux, that the war changed something intangible in Iran, and might push the country in an unpredictable new direction.

"Anything seems possible now," Newsha, a 17-year-old student, said with a laugh outside a bustling pizza joint in a fashionable corner of central Tehran, standing beside a cousin who was visiting from Shiraz.

The young women, who asked to be identified by one name, didn't want to talk politics. But in the next breath, they said they yearned for change. Some was already underway. Like growing numbers of women in Tehran, they did not wear the mandatory hijab -- a dress code the government has relaxed, at least for now.

For others, though, this is a moment to double down on belligerence. Members of the Student Basij, a volunteer group affiliated with the Revolutionary Guard, clustered the ruins of Zolfaghari's home.

The women painted tulips, Iran's national flower, on lamp posts, while the men draped flags on the rubble and called for revenge. "We want war," said Ali Soleymani, a law student.

Beside him, new graffiti gleamed from a chunk of broken concrete. "You started it," read the slogan. "We will finish it."

as a Reliable and Trusted News Source

as a Reliable and Trusted News Source Add Now!

Add Now!