New Delhi: Historian Romila Thapar on Tuesday said Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) and other centres of social sciences have suffered in the last 10 years, and those who were involved in their establishment are appalled by the “decimation”.

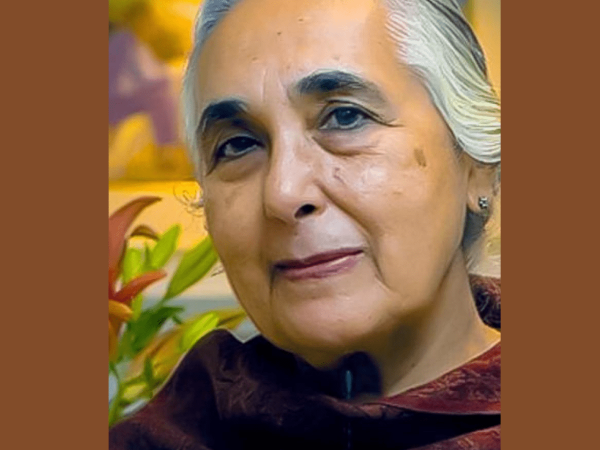

Thapar, who was speaking at the third Kapila Vatsyayan Memorial Lecture at the India International Centre here, said maintaining academic standards at JNU in the last decade has been “extremely problematic”.

“Some of us who were involved in establishing JNU in the 1970s have been appalled by the decimation that it has undergone in the last 10 years. This is not confined to JNU alone, as other strong centres of the social sciences have also suffered,” Thapar said.

Romila Thapar said they had succeeded in establishing a university that was highly respected at home and in the world outside.

“…but in the last decade, maintaining academic standards has been made extremely, to put it politely, problematic. This was done in various ways, through appointing some substandard faculty, non-professionals dictating the curriculum and syllabi, attempts to rescind the earlier appointed professor emeritus, curtailing freedom to research and teach what academics regard as meaningful,” the historian said.

Citing the January 2020 incident at the university, in which an armed mob stormed the campus, resulting in injuries to students and faculty, the 93-year-old said that the situation “went beyond academic mechanism”.

While mentioning the arrest of Umar Khalid without naming him, Thapar said, “political control over education silences intellectual creativity”.

“There have been arrests of students for criticising authority, and some of those arrested are in jail still without a trial, despite the last six years of being there.

“Intellectually purposeful education requires thinking with freedom…or is this control just another demonstration of the prevalent preference for anti-intellectualism. Speech can be silenced, but thought cannot be stilled,” Romila Thapar said.

She also criticised the “current methods of history education” in India by saying that “history is an easy prey because of the generally scant knowledge of history in the country”.

“It is unacceptable to professional historians, but it is acceptable to the members of the public who, in turn, quote it perhaps because of the generally scant knowledge of history in this country.

“The sciences, being more technical, are not fantasised. The social sciences analyse how societies function and are therefore less technical and more vulnerable. And history is an easy prey,” Thapar said.

The author of “Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300” argued that what is being propagated in history teaching today is a “return to the discarded colonial theories”.

“This is not the decolonisation that it claims to be, since it supports colonial teachings. This supposedly new history claims to replace what others have been writing and teaching in the last 75 years in post-colonial times, much of which is conveniently labelled Marxist, thus said to be erroneous and dismissed,” she said.

Speaking about the “Hindutva version” of history teaching that upholds colonial theories of superiority of the Aryan race and the Two-Nation Theory, Thapar said it is argued that the rightful future of India lies in its reverting to a Hindu state and asked, “Can a society as diverse as India be reduced to having a single uniform heritage?”

“Singular majoritarianism contradicts democracy, as also does acquiescence with the hierarchy of caste. This concerns the basic question of Indian pluralism: will we still be able to nurture a society whose parameters are open to debate and discussion? Are we willing to confine our society to a single uniform way of living and thinking? Will there only be one explanation of the past and all others dismissed? Is culture going to be defined by the culture idiom of the dominant community, will variants be disallowed?” she questioned.

Thapar added that history, as taught and read, has to be reliable and accurate, which further requires ensuring that it is not “being manipulated for political or other reasons”.

At this point, education becomes crucial, involving trained and competent teachers who can encourage students to ask questions.

“There was a time when students in state schools were given an education that had some degree of quality in terms of a basic understanding of the world in which they lived. This is woefully scarce today.

“It is not thought necessary that students should be taught to comprehend and question, if they wish to, the society in which they live,” she said.