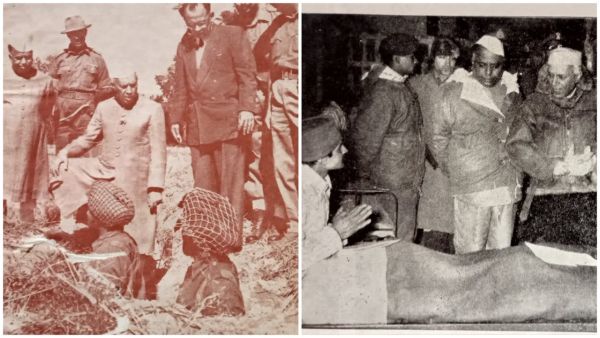

On the morning of May 26, 1960, as tensions simmered along what is now known as the Line of Control (LoC), India’s then Defence Minister V.K. Krishna Menon convened a top-secret meeting in his office. Present were the formidable Army Chief, General Kodandera Subayya Thimayya—a man unafraid to challenge Menon’s acerbic temperament—and the Chief of Air Staff, Air Marshal Subroto Mukerjee.

The instructions were to identify suitable sites for additional airstrips near India’s border posts. These would serve as lifelines for newly established Himalayan outposts, isolated and far from the nearest roads, ensuring they could be adequately supplied.

Fast forward to 20 October 1960, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru issued strict directives. Flights near the Sino-Indian border were tightly restricted; the Air Force could conduct no sorties or reconnaissance within 24 km of the frontier, with only transport aircraft allowed to approach.

By December 1961, Menon approved an urgent exemption for certain reconnaissance flights, equipped with cameras, to map key areas such as Aksai Chin, Tawang, Sela, and Walong. These flights provided crucial terrain intelligence to the Army.

Then came 1962—and the war.

Despite the looming conflict, the Indian Air Force remained largely sidelined from offensive operations, restricted to transport and supply missions. This has since become one of the most tantalizing “what ifs” in modern Indian military history: Could the IAF have altered the outcome of the Sino-Indian War of 1962?

The question was already hotly debated even as hostilities raged. According to still-classified records accessed by ThePrint, the Indian Air Force lacked confidence, its assessment clouded by sketchy intelligence and the harsh Himalayan terrain. The Chinese, presumed to enjoy air superiority, compounded India’s strategic dilemma. While limited transport flights operated, there were no Chinese sorties over India during the conflict.

The Ministry of Defence’s official history paints a grim picture of India’s aerial infrastructure: no radars, a single radio link in Leh with a mere 16 km range, and only one sortie per aircraft per day. On the eastern front, jungle terrain rendered close air support perilous for dispersed infantry units.

Krishna Menon advocated for Air Force deployment, but the military establishment remained cautious. General Thimayya believed forces should be strengthened before considering a forward advance—a stance that shifted only with the adoption of the so-called ‘Forward Policy.’

This policy, aimed at establishing forward posts to reclaim territory from China, is widely regarded as the immediate trigger for the 1962 conflict. The political decision to implement it was sealed in a top-secret meeting on 2 November 1961, chaired by Nehru and attended by Menon, Chief of General Staff Lieutenant General B.M. Kaul, Intelligence Bureau Director B.N. Mullik, and new Army Chief Lieutenant General P.N. Thapar.

Opposition came notably from General Thimayya, who had retired in May 1961. He had cautioned against the proposal, warning that the Indian Army should not go on the offensive until fully capable. Nehru, however, endorsed the strategy, framing it as support for bases where troops could regroup, despite sharp parliamentary criticism. “Why go on advertising unpreparedness?” demanded Bapu Nath Pai, a Bombay MP, underscoring the political tension in December 1961.

From Beijing’s perspective, the Forward Policy signaled India’s intent to occupy Chinese territory, exposing the failure of 1960 talks between Nehru and Premier Zhou Enlai to resolve territorial disputes diplomatically.

The reluctance to deploy the Air Force was not purely military—it stemmed from intelligence and diplomatic advice. Key influences included IB Director Mullik, US Ambassador J.K. Galbraith, and British defence advisor P.M.S. Blackett.

Mullik warned that Chinese bombers could “penetrate as far South as Madras,” especially given India’s lack of night interceptors. Galbraith considered Indian air deployment futile, noting that Indian planes could reach only Tibet, with no significant targets there. India even requested aerial support from the US on 19 November 1962, but the plea went unanswered. Blackett advised that Air Force involvement should remain tactical, cautioning that broader deployment could escalate the war.

Thus, the fateful decision was made: the Indian Air Force would remain largely inactive in offensive operations. Post-war reflections were regretful; Chief of General Staff Kaul admitted in his 1967 memoir that India “made a great mistake in not employing our Air Force in a close support role during these operations.”

As the MoD’s official history notes, “There is no accurate or authentic documentation of the thinking that was behind this decision to desist from use of offensive air support."

(This article has been curated with the help of AI)