60 years on, the war’s timeless lessons — from courage in Phillora to diplomacy in Tashkent — continue to guide India’s modern security

Published Date – 8 November 2025, 11:43 PM

By Brig Advitya Madan (retd)

This year, India marks the Diamond Jubilee — 60 years — of its victory in the 1965 Indo-Pak War. It’s more than a commemoration of a military triumph; we must take out time to reminisce about the gallant efforts of the soldiers of the Indian armed forces who thwarted the nefarious designs of Pakistan to grab Kashmir by treachery — a gambit Pakistan repeated in subsequent wars but met with back-to-back humiliating defeats.

It’s also a moment to recall the geopolitical and strategic contours that shaped that conflict — lessons that remain uncannily relevant in today’s shifting regional landscape. As the generation that fought those battles fades into history, retelling this story becomes vital — not merely to honour the heroes of Phillora, Asal Uttar, and Haji Pir, but also to ensure that India’s future decision-makers never lose sight of the strategic interplay of diplomacy, alliance politics, and miscalculation that led to war.

Global Chessboard

The seeds of the 1965 conflict were sown in the early years of the Cold War. Pakistan’s leadership under Field Marshal Ayub Khan chose to align firmly with the United States, seeing in Washington’s anti-Communist agenda an opportunity to strengthen its military capability against India.

In September 1954, Pakistan joined the South East Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), followed by the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO) in 1955. The US sought to use Pakistan as a bulwark against Soviet and Chinese influence, while Pakistan hoped to leverage the alliance to gain strategic parity with India. Between 1956 and 1964, Pakistan received a windfall of US military hardware: M47 and M48 Patton tanks, F-86 Sabre jets, F-104 Starfighters, B-57 bombers, and C-130 transport aircraft. By the mid-1960s, Pakistan’s armed forces were among the most US-equipped in the non-NATO world.

In contrast, India’s non-aligned posture meant that American aid was limited and conditional. The US viewed India with caution, particularly after New Delhi’s leadership in the Non-Aligned Movement. This asymmetric military modernisation left Pakistan brimming with overconfidence — a misjudgment that would later prove costly.

That overconfidence was also shaped by propaganda. The Pakistani media, at the time, portrayed its army as the “shield of Islam” and its US-supplied arsenal as invincible. Indian restraint and moderation were misconstrued as weakness. In reality, India’s rebuilding of its armed forces after the 1962 (Sino-India) setback was deliberate, methodical, and underpinned by a quiet determination not to be caught unprepared again.

A Comparative Military Balance

By 1965, Pakistan’s Army fielded roughly 765 tanks compared to India’s 720, but the quality differential was significant. Pakistan operated nine regiments of Pattons, nine of Shermans, and three of Chaffees, whereas India had eight Sherman regiments, four Centurion regiments, and two of AMX-13s.

In artillery, Pakistan had modern 155 mm guns and 8-inch howitzers, while India relied heavily on 120 mm mortars and 7.2-inch guns. Its air force boasted faster, more advanced platforms. On paper, Pakistan appeared militarily superior, particularly in armour and air power. This technical advantage, bolstered by US support and further cooperation with Britain, created an illusion of invincibility in Rawalpindi, an illusion that would unravel dramatically within a year.

What the numbers missed was the Indian soldier’s morale, training, and adaptability. Leadership — from corps commanders to company officers — proved decisive. The Indian Army’s institutional memory, its discipline, and the moral authority of its leadership became the true force multipliers when war finally broke out.

Changing Geopolitics

The geopolitical equation deepened when Pakistan began tilting towards China after India’s 1962 border conflict with Beijing. The US, attempting to assist India with limited post-war aid worth around USD47 million, inadvertently pushed Pakistan further into China’s orbit. By comparison, Pakistan had already received over USD1.5 billion in American aid — of which USD800 million was military. In 1963, Pakistan ceded 5,200 sq km of territory in the Shaksgam Valley to China, sealing a de facto strategic partnership that endures to this day.

India, increasingly alienated from Washington, began leaning toward the Soviet Union for security and defence cooperation — a realignment that would later crystallise in the 1971 Indo-Soviet Treaty. These diplomatic crosscurrents meant that by 1965, South Asia had already become a miniature theatre of the global Cold War.

Domestically, India was navigating political and social flux. The theft of a relic — a strand of the Prophet Mohammad’s hair — from Hazratbal Shrine in 1964 triggered unrest in Jammu &Kashmir, which Pakistan misread as an indicator of instability. In Punjab, the agitation for a Punjabi Suba was gaining momentum. And, following Jawahar Lal Nehru’s death in May 1964, Lal Bahadur Shastri had taken over as Prime Minister — a transition that Ayub Khan and his Foreign Minister, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, misinterpreted as weakness.

Ayub Khan, already politically insecure after a close and contested presidential election against Fatima Jinnah, believed that a quick military success in Kashmir could restore his domestic standing and deliver a psychological blow to India. But in reading India’s democracy as fragile, he fatally misunderstood its resilience.

From Rann of Kutch to Operation Gibraltar

Tensions first flared in the Rann of Kutch in early 1965, where India’s 31 Infantry Brigade Group clashed with Pakistan’s 8 Division and 24 Cavalry. A ceasefire brokered by the UK on 1 July 1965 temporarily calmed the front, but it emboldened Pakistan’s military planners.

By August 1965, Pakistan launched Operation Gibraltar, a covert infiltration by around 30,000 troops in six groups, aiming to incite rebellion in Jammu & Kashmir. These six groups were named Tariq, Qasim, Khalid, Salahiddin, Ghaznavi, and Babur. They were launched by Pak GOC 12 Division, Maj Gen Akhtar Hussain Malik, with three objectives — disrupt Indian control of J&K, incite armed revolt, and create conditions for “liberation.”

The Tariq group’s objective was to disrupt the route towards Zojila Pass and take control of Amarnath. Qasim’s aim was to destroy bridges on the Bandipura-Gandarbal road. The Khalid group was to attack the infrastructure at Handwara and destroy the Kupwara power station. Salahuddin group’s target was to sever road links and capture the Srinagar Radio Station and airfield. Ghaznavi was tasked to attack Rajouri-Naushera; Babur was to target Udhampur HQ and disrupt communications.

Commanders of Courage

Indian forces in the Valley were limited — only four J&K Militia battalions and an animal-transport company. Later, 4 Sikh Light Infantry and 2/9 Gurkha Rifles were dispatched with additional brigades from Leh and Jammu.

Let’s analyse the progress of these six groups. The Tariq group could never reach its objective due to high-altitude casualties. Qasim failed to generate local support. Salahuddin lost surprise and was detected during infiltration. Only Ghaznavi achieved some success, but without strategic impact.

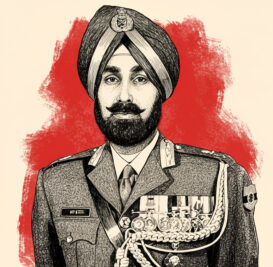

The pivotal role of Lt Gen Harbaksh Singh, the Western Army Commander, is worth mentioning. On August 8, after infiltration by these Pakistani groups, the J&K government panicked and proposed martial law. Lt Gen Singh strongly intervened, reasoning that martial law would validate Pakistani propaganda and demoralise Kashmiris. His advice was accepted — a decision that proved crucial.

The Pak gambit failed miserably. Several locals reported the infiltrators instead of rising in revolt. On August 5, a local Gujjar boy, Mohammad Din, reported armed men near Tangmarg. The 19 Division was alerted and killed several infiltrators — all part of Salahuddin’s group led by Pak Major Mansha Khan. By August 15, Operation Gibraltar had failed. Pakistan had wrongly assumed a local uprising and underestimated India’s coordinated counter-response.

When the plans collapsed, Pakistan escalated to Operation Grand Slam on 1 September, targeting Akhnoor to sever India’s lines of communication to J&K.

India Strikes Back

In a bold counterstroke, India widened the conflict across the International Border. On 6 September 1965, XI Corps advanced towards Lahore, Barki, and Kasur, while I Corps launched major thrusts in the Sialkot sector with its 1 Armoured Division, 6 Division, 14 Division, and 26 Division.

The Battle of Phillora, led by India’s 1 Armoured Division, became one of the largest tank battles since World War II — and ended decisively in India’s favour. Despite its superior hardware, Pakistan’s forces faltered under the weight of Indian tenacity and leadership.

India’s success on land was matched by courage in the air. The Indian Air Force, though operating less advanced aircraft, fought with extraordinary ingenuity and valour, keeping control of the skies in crucial sectors.

Tank that turned the tide

The Battle of Phillora, led by India’s 1 Armoured Division, became one of the largest tank battles since World War II — and ended decisively in India’s favour, showcasing courage, tactics, and indigenous leadership

Victory with Restraint

By the ceasefire, India had captured 1,920 sq km of Pakistani territory, while Pakistan held 540 sq km of Indian land. India lost 2,862 soldiers, while Pakistan’s fatalities were estimated at 5,847. Notably, the Indian Army had used only 14 per cent of its ammunition reserves, while Pakistan had exhausted over 80 per cent — a telling indicator of sustainability.

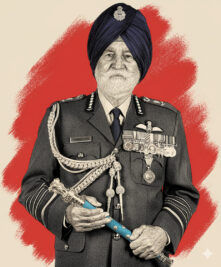

It’s worth highlighting that then Air Chief Marshal Arjan Singh was disheartened when the ceasefire was declared after 17 days, since the IAF had consumed less than 10 per cent of its resources. When the IAF was gaining air superiority, the ceasefire was announced.

IAF pilots had begun dominating Pakistani counterparts in dogfights through sheer guts and tactics despite facing superior aircraft like Sabres and Starfighters. None can forget how, on September 3, SqnLdr Trevor Keelor, flying a Gnat, shot down a Sabre — the first kill by the IAF. Initially, the IAF operated only in the Chhamb sector, using Vampires by day and Mystères by night.

South Asia: Emerging battleground of Cold War

After India’s 1962 war with China, Pakistan aligned with Beijing and deepened ties with the US, while India, increasingly alienated from Washington, began leaning toward the Soviet Union for security and defence support. These opposing alliances — US-China-Pakistan versus India-USSR — transformed South Asia into a miniature theatre of the global Cold War

The Pakistani Air Force would have been fully destroyed had the war continued a little longer. This brings us to a vital lesson — political and military objectives must align from day one, as we saw recently in Operation Sindoor. Another key lesson was the offensive use of air power, which we hesitated to deploy in 1965. Even in 1962, air power was left out — a costly error.

Strategic restraint, combined with international pressure, led to the Tashkent Agreement of 10 January 1966, brokered by the Soviet Union. Although India returned territories such as Haji Pir Pass, the moral and military victory was unequivocal. Much credit goes to Lt Gen Harbaksh Singh, whose leadership on the Western Front became legend.

Lessons from the Past

Sixty years later, history seems to rhyme. Pakistan’s economic distress, internal political divisions, and over-reliance on external patrons — first the US, now China — echo the vulnerabilities of the 1960s. The China-Pakistan nexus, much like 1965, is again being leveraged as a counterweight to India’s growing power.

As Pakistan’s current military leadership under Gen Asim Munir exudes familiar overconfidence amid domestic fragility, one must ask: could another misadventure be on the horizon? The lessons of 1965 are clear — strategic overconfidence, misreading of India’s resolve, and external dependence can be fatal miscalculations.

For India, the message is equally sharp: vigilance, unity, and readiness remain the best guarantees of peace. We need better intelligence, jointness, integration amongst the forces, and offensive use of air power. We should not delay any further implementation of theatre commands. Even the concept of Agniveers needs a relook.

At the same time, India’s security calculus must now extend beyond land and air to cyberspace, outer space, and information warfare. The strategic frontiers have expanded, but the guiding principle endures — peace is secured by preparedness.

(The author is a retired Army officer)