The crash of the Bombardier Learjet 45 in Baramati on Wednesday that killed Maharashtra deputy chief minister Ajit Pawar, along with five others, highlights the patchy safety record of non-scheduled operators in the country, said experts and aviation officials.

Last year, after a series of helicopter crashes at Kedarnath, Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) inspectors undertook an extensive audit of rotary wing aircraft.

They found multiple cases in which components were used beyond expiry date. “In some cases, the same component was taken out and then refitted with false diary entries —violations were rampant,” said an official who didn’t want to be named.

VK Singh, director of VSR Ventures, operator of the business jet that was carrying Pawar, ruled out technical issues, and instead blamed possible visibility issues on the runway.

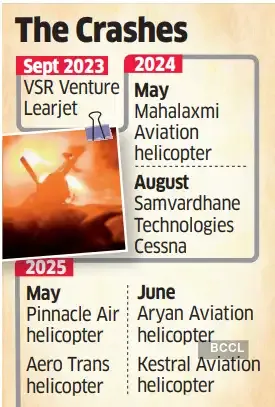

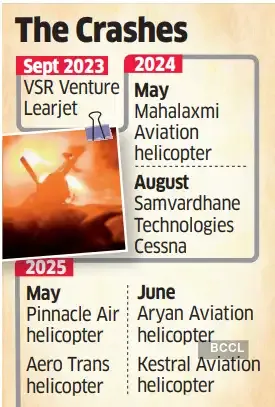

Apart from the Air India accident in Ahmedabad, last year saw eight fatal crashes. Five of them were helicopters operated by non-scheduled operators.

According to a report by consultancy Asian Sky Group, the number of business jets in India grew 12%, from 150 to 168, the third-fastest growth in the region, behind Singapore and Vietnam.

Industry executives said cutting corners on safety has been a widespread practice among non-scheduled operators. Big corporate houses such as Reliance and Adani Group maintain their own jets, as do some other corporations and individuals. Beyond that, brokers and owners leasing aircraft to thirdparty charter operators have mushroomed.

“In such cases, the operator takes up those aircraft from individual owners in return for an agreed amount,” said the chief pilot of a charter company. “The operators then have to sweat the asset as much as possible, which leads to cutting corners in maintenance and training standards.”

These operators are not bound by strict commercial airline-level safety and training standards, often flying under the radar of DGCA’s surveillance process, said people with knowledge of the matter. Many charter operators function with lean technical and safety teams.

“Consider an operator with three aircraft. The regulation demands that he gets post holders like head of training, safety, standards. This leads to high cost and the operator then cuts corners in safety,” said an executive at a charter operator. “While a mainline airline will not risk flying an aircraft with an expired component, as it may kill its reputation, a charter operator may risk that for one small flight.”

Adding to the complexity, most charter operators fly to remote airports that may not have robust air traffic control and radar facilities, adding to the chances of a pilot or technical fault turning critical.

Preliminary investigation suggests Wednesday’s crash occurred amid poor runway visibility. Baramati airport doesn’t have weather radar or advanced navigation equipment.

Compared with commercial passenger airline crashes, the toll in charter accidents are much less and therefore tend to generate smaller headlines. Besides, such mishaps tend to occur at small, out-of-the-way airports. “Had it not been Ajit Pawar, no one would have bothered,” said the person cited.

Last year, after a series of helicopter crashes at Kedarnath, Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) inspectors undertook an extensive audit of rotary wing aircraft.

They found multiple cases in which components were used beyond expiry date. “In some cases, the same component was taken out and then refitted with false diary entries —violations were rampant,” said an official who didn’t want to be named.

VK Singh, director of VSR Ventures, operator of the business jet that was carrying Pawar, ruled out technical issues, and instead blamed possible visibility issues on the runway.

Apart from the Air India accident in Ahmedabad, last year saw eight fatal crashes. Five of them were helicopters operated by non-scheduled operators.

According to a report by consultancy Asian Sky Group, the number of business jets in India grew 12%, from 150 to 168, the third-fastest growth in the region, behind Singapore and Vietnam.

Industry executives said cutting corners on safety has been a widespread practice among non-scheduled operators. Big corporate houses such as Reliance and Adani Group maintain their own jets, as do some other corporations and individuals. Beyond that, brokers and owners leasing aircraft to thirdparty charter operators have mushroomed.

“In such cases, the operator takes up those aircraft from individual owners in return for an agreed amount,” said the chief pilot of a charter company. “The operators then have to sweat the asset as much as possible, which leads to cutting corners in maintenance and training standards.”

These operators are not bound by strict commercial airline-level safety and training standards, often flying under the radar of DGCA’s surveillance process, said people with knowledge of the matter. Many charter operators function with lean technical and safety teams.

“Consider an operator with three aircraft. The regulation demands that he gets post holders like head of training, safety, standards. This leads to high cost and the operator then cuts corners in safety,” said an executive at a charter operator. “While a mainline airline will not risk flying an aircraft with an expired component, as it may kill its reputation, a charter operator may risk that for one small flight.”

Adding to the complexity, most charter operators fly to remote airports that may not have robust air traffic control and radar facilities, adding to the chances of a pilot or technical fault turning critical.

Preliminary investigation suggests Wednesday’s crash occurred amid poor runway visibility. Baramati airport doesn’t have weather radar or advanced navigation equipment.

Compared with commercial passenger airline crashes, the toll in charter accidents are much less and therefore tend to generate smaller headlines. Besides, such mishaps tend to occur at small, out-of-the-way airports. “Had it not been Ajit Pawar, no one would have bothered,” said the person cited.