If there is one reptile that scares the heebie-jeebies out of the hardiest of humans, it will be the snake. The fear and veneration of its potent venom is perhaps not unfounded in South Asia. India has the highest number of casualties from snakebites globally. Even today.

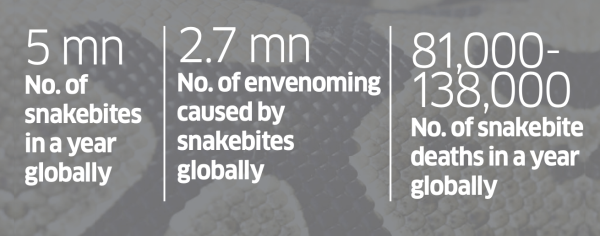

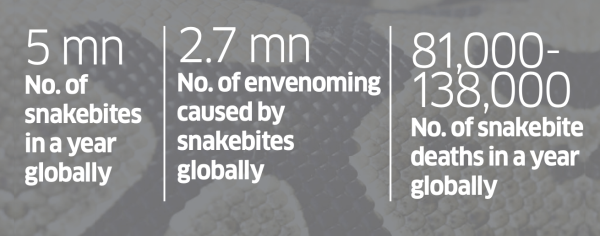

A 2020 study, “Trends in Snakebite Deaths in India from 2000 to 2019 in a Nationally Representative Mortality Study”, found that 1.2 million Indians died from snakebite envenoming between 2000 and 2019, with about 58,000 deaths on an average every year, the highest rate in the world. Snakebite envenoming is a potentially life threatening disease caused by the bite of a venomous snake.

The study, which was based on a global research project on mortality called the Million Death Study (MDS), also found that people in rural areas had a high risk of snakebites and 97% of snakebite deaths happened in Indian villages. The response of the healthcare system was considered inadequate, with only 23% of deaths occurring in hospitals, and antivenoms showing potency issues.

The study—and the conversation it triggered—seem to have shocked the system out of its slumber.

The study—and the conversation it triggered—seem to have shocked the system out of its slumber.

The Indian government and the biotech industry are addressing the problem with renewed vigour after decades of status quo. The National Action Plan for Snakebite Envenoming (NAPSE), announced by India’s National Centre for Disease Control in March this year, is meant to provide a framework for the “management, prevention and control of snakebite envenoming in India”. The goal is to halve the number of deaths and disabilities due to snake bite envenoming by 2030.

Biotech and pharma players in India are currently engaged in research that will help develop better antivenoms. Bharat Serums and Vaccines (BSV) and the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) are working on creating a broad suite of antivenoms that target snakes from specific areas.

A major global health issue, which disproportionately affects millions in the Global South, is finally in the spotlight.

Sharper Targeting

Sharper Targeting

Dr Jaby Jacob, senior president, R&D, BSV, calls venoms evolutionary toxins, generated over millions of years of “arms race”, with the sole purpose of giving the owner an edge over its prey or aggressor. BSV is one of the earliest biopharmaceutical players addressing the market, having launched antivenoms in the 1990s. Serum Institute of India was also involved in the manufacturing of antivenoms but has now moved aw ay from the market.

T he antivenom that is used in India is primarily intended for the big four snakes— common krait, Indian cobra, Russell’s viper and the saw-scaled viper. However, this approach may not be ideal since the genetic make-up of snakes and, by extension, their venoms, differs. According to NAPSE, “India has more than 310 species of snakes, mostly nonvenomous. However, there are 66 species that are labelled as venomous or mildly venomous.”

Even the venom of the same species of snakes may vary from region to region. Says Jacob: “The major concern with venoms is that they show significant variation even at intra-species level, depending on the biotic and abiotic conditions of the habitat. Additionally, they are also found to vary depending on prey/predator nature and their evolutionary history.”

Even the venom of the same species of snakes may vary from region to region. Says Jacob: “The major concern with venoms is that they show significant variation even at intra-species level, depending on the biotic and abiotic conditions of the habitat. Additionally, they are also found to vary depending on prey/predator nature and their evolutionary history.”

A 2024 paper in the science journal Nature details that 'venom comprises 50-200 components, present in multiple protein isoforms, and these can differ even within a species depending on age, location, and season.' Since India has many extremely venomous snake species, conventional antivenoms aren’t always effective. This is one of the reasons why IISc and BSV are looking at creating a range of antivenoms. Currently, venom from different snakes from different parts of the country are being sourced and analysed at the genomics lab in IISc. Understanding the subtle differences in the genetic make-up of venoms could help them design antivenoms for each subvariant.

“While the R&D efforts have progressed well, we are still working on the process of procuring sufficient quantities of region-specific venoms for large-scale production,” says Jacob.

Even the venom of the same species of snakes may vary from region to region. Says Jacob: “The major concern with venoms is that they show significant variation even at intra-species level, depending on the biotic and abiotic conditions of the habitat. Additionally, they are also found to vary depending on prey/predator nature and their evolutionary history.”

A 2024 paper in the science journal Nature details that 'venom comprises 50-200 components, present in multiple protein isoforms, and these can differ even within a species depending on age, location, and season.' Since India has many extremely venomous snake species, conventional antivenoms aren’t always effective. This is one of the reasons why IISc and BSV are looking at creating a range of antivenoms. Currently, venom from different snakes from different parts of the country are being sourced and analysed at the genomics lab in IISc. Understanding the subtle differences in the genetic make-up of venoms could help them design antivenoms for each subvariant.

A 2024 paper in the science journal Nature details that 'venom comprises 50-200 components, present in multiple protein isoforms, and these can differ even within a species depending on age, location, and season.' Since India has many extremely venomous snake species, conventional antivenoms aren’t always effective. This is one of the reasons why IISc and BSV are looking at creating a range of antivenoms. Currently, venom from different snakes from different parts of the country are being sourced and analysed at the genomics lab in IISc. Understanding the subtle differences in the genetic make-up of venoms could help them design antivenoms for each subvariant.

“While the R&D efforts have progressed well, we are still working on the process of procuring sufficient quantities of region-specific venoms for large-scale production,” says Jacob.

Making Antivenom

The manufacturing of antivenom fundamentally relies on old methods developed by a French doctor. Albert Calmette, who spent time in Vietnam in the late 1800s , produced an anti-cobra serum once back in Lille. This has been the foundation of antivenom treatment globally.

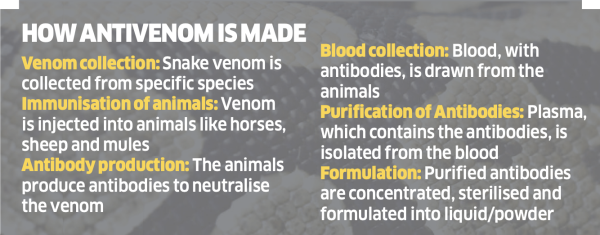

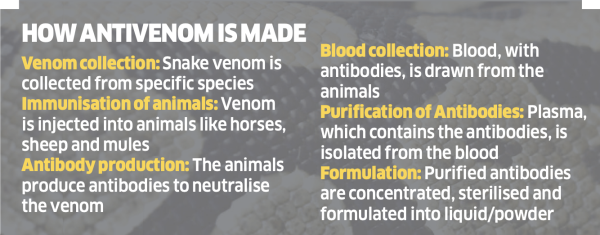

Snake catchers are roped in to supply venom, which is then injected into mules, horses and donkeys. These animals produce antibodies to counteract the toxin. Blood is first extracted from the animals. The plasma in the blood is then purified to isolate the antibodies.

According to an article by Susan Scutti, a journalist with the US’ National Institutes of Health, “While the basic production method has remained little changed, many technological advances and purification processes have been introduced to achieve higher quality products and reduce side effects.” One such method that reduces side effects in patients is to inject antivenom into the vein as opposed to the muscle or under the skin.

However, there is one aspect that hasn’t really improved: the involvement of animals in the process. This has attracted the attention of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), which says the procedure drains as much as 15% blood of horses, donkeys and mules and can result in them suffering from “anaemia as well as untreated wounds, diseased hooves, malnourishment, infections, parasites, swollen limbs, lameness and eye abnormalities”.

To counter this, PETA ran a global campaign in 2016, after which the Indian government announced in 2017 that it “would provide funding for the development of modern manufacturing methods for snake antivenoms”. While this is good news for animals, it isn’t so for snake catchers. About 80% of antivenom used in India is sourced from the venom captured by snake catchers who belong to the Irula tribe in Tamil Nadu. Antivenoms are not enough. These have to be made accessible to people worst affected by snakebites.

A WHO report on the “Trends in Snakebite Deaths in India…” points out that “people living in densely populated low altitude agricultural areas in the states of Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh (which includes Telangana, a recently defined state), Rajasthan and Gujarat, suffered 70% of deaths during the period 2001-2014, particularly during the rainy season when encounters between snakes and humans are more frequent at home and outdoors”.

Poor farmers, who get bitten, often go to village quacks who follow substandard, approaches. Fatality is also high in children who are exposed to snakes while playing around agricultural fields. A study, “Clinical Profile of Snake Bite in Children in Rural India”, found that snakebites account for 3% of all deaths in children aged 5-14 years.

Jose Louies, CEO of Wildlife Trust of India, says quacks often end up burning the bite site, cutting it open and applying various pastes on the area, all of which end up catalysing the movement of toxins in the body.

When patients are not taken to the official healthcare system, the death is not captured as a snakebite death, which leads to severe underreporting of the issue. Experts say that the actual number of people who die from snakebites in India could be several times the number reported by the government. According to the Central Bureau of Health Investigation reports (2016-20), “the average annual frequency of snakebite cases in India is around 3 lakhs and about 2,000 deaths occur due to snakebite envenoming”. This is far less than the 58,000 reported in the 2020 study.

This is where NAPSE’S proposed programme to build awareness comes in. Its primary action is to identify at-risk regions and communities, adapt WHO’s toolkit for communication and training to local contexts, organise participatory community training and engage with traditional healers, community health workers and other local leaders and activists.

It intends to persuade victims to go to medical centres, popularise first aid and support communities in adopting better healthcare-seeking behaviour.

However, there is an area where the government needs to step in: distribution of antivenoms. Louies points to issues with the distribution of antivenoms in primary health centres, particularly in the rural areas of some of the poorest regions of the country, which account for 7 out of 10 deaths from snakebites.

That this grave issue was not a priority for decades points to the inequities in the global healthcare system. While the Global North has its share of venomous snakes, their interaction with human settlements is minimal and the venom itself is less potent. On the contrary, snakebite deaths primarily happen to the poorest in the Global South.

NAPSE acknowledges this in its report: “snakebite envenoming has failed to attract requisite public health policy inclusion and investment for driving sustainable efforts to reduce the medical and societal burden. This is largely due to the demographics of the affected populations and their lack of political voice”.

It is time to change that.

A 2020 study, “Trends in Snakebite Deaths in India from 2000 to 2019 in a Nationally Representative Mortality Study”, found that 1.2 million Indians died from snakebite envenoming between 2000 and 2019, with about 58,000 deaths on an average every year, the highest rate in the world. Snakebite envenoming is a potentially life threatening disease caused by the bite of a venomous snake.

The study, which was based on a global research project on mortality called the Million Death Study (MDS), also found that people in rural areas had a high risk of snakebites and 97% of snakebite deaths happened in Indian villages. The response of the healthcare system was considered inadequate, with only 23% of deaths occurring in hospitals, and antivenoms showing potency issues.

The Indian government and the biotech industry are addressing the problem with renewed vigour after decades of status quo. The National Action Plan for Snakebite Envenoming (NAPSE), announced by India’s National Centre for Disease Control in March this year, is meant to provide a framework for the “management, prevention and control of snakebite envenoming in India”. The goal is to halve the number of deaths and disabilities due to snake bite envenoming by 2030.

Biotech and pharma players in India are currently engaged in research that will help develop better antivenoms. Bharat Serums and Vaccines (BSV) and the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) are working on creating a broad suite of antivenoms that target snakes from specific areas.

A major global health issue, which disproportionately affects millions in the Global South, is finally in the spotlight.

Dr Jaby Jacob, senior president, R&D, BSV, calls venoms evolutionary toxins, generated over millions of years of “arms race”, with the sole purpose of giving the owner an edge over its prey or aggressor. BSV is one of the earliest biopharmaceutical players addressing the market, having launched antivenoms in the 1990s. Serum Institute of India was also involved in the manufacturing of antivenoms but has now moved aw ay from the market.

T he antivenom that is used in India is primarily intended for the big four snakes— common krait, Indian cobra, Russell’s viper and the saw-scaled viper. However, this approach may not be ideal since the genetic make-up of snakes and, by extension, their venoms, differs. According to NAPSE, “India has more than 310 species of snakes, mostly nonvenomous. However, there are 66 species that are labelled as venomous or mildly venomous.”

A 2024 paper in the science journal Nature details that 'venom comprises 50-200 components, present in multiple protein isoforms, and these can differ even within a species depending on age, location, and season.' Since India has many extremely venomous snake species, conventional antivenoms aren’t always effective. This is one of the reasons why IISc and BSV are looking at creating a range of antivenoms. Currently, venom from different snakes from different parts of the country are being sourced and analysed at the genomics lab in IISc. Understanding the subtle differences in the genetic make-up of venoms could help them design antivenoms for each subvariant.

“While the R&D efforts have progressed well, we are still working on the process of procuring sufficient quantities of region-specific venoms for large-scale production,” says Jacob.

Even the venom of the same species of snakes may vary from region to region. Says Jacob: “The major concern with venoms is that they show significant variation even at intra-species level, depending on the biotic and abiotic conditions of the habitat. Additionally, they are also found to vary depending on prey/predator nature and their evolutionary history.”

“While the R&D efforts have progressed well, we are still working on the process of procuring sufficient quantities of region-specific venoms for large-scale production,” says Jacob.

Making Antivenom

The manufacturing of antivenom fundamentally relies on old methods developed by a French doctor. Albert Calmette, who spent time in Vietnam in the late 1800s , produced an anti-cobra serum once back in Lille. This has been the foundation of antivenom treatment globally.

Snake catchers are roped in to supply venom, which is then injected into mules, horses and donkeys. These animals produce antibodies to counteract the toxin. Blood is first extracted from the animals. The plasma in the blood is then purified to isolate the antibodies.

According to an article by Susan Scutti, a journalist with the US’ National Institutes of Health, “While the basic production method has remained little changed, many technological advances and purification processes have been introduced to achieve higher quality products and reduce side effects.” One such method that reduces side effects in patients is to inject antivenom into the vein as opposed to the muscle or under the skin.

However, there is one aspect that hasn’t really improved: the involvement of animals in the process. This has attracted the attention of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), which says the procedure drains as much as 15% blood of horses, donkeys and mules and can result in them suffering from “anaemia as well as untreated wounds, diseased hooves, malnourishment, infections, parasites, swollen limbs, lameness and eye abnormalities”.

To counter this, PETA ran a global campaign in 2016, after which the Indian government announced in 2017 that it “would provide funding for the development of modern manufacturing methods for snake antivenoms”. While this is good news for animals, it isn’t so for snake catchers. About 80% of antivenom used in India is sourced from the venom captured by snake catchers who belong to the Irula tribe in Tamil Nadu. Antivenoms are not enough. These have to be made accessible to people worst affected by snakebites.

A WHO report on the “Trends in Snakebite Deaths in India…” points out that “people living in densely populated low altitude agricultural areas in the states of Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh (which includes Telangana, a recently defined state), Rajasthan and Gujarat, suffered 70% of deaths during the period 2001-2014, particularly during the rainy season when encounters between snakes and humans are more frequent at home and outdoors”.

Poor farmers, who get bitten, often go to village quacks who follow substandard, approaches. Fatality is also high in children who are exposed to snakes while playing around agricultural fields. A study, “Clinical Profile of Snake Bite in Children in Rural India”, found that snakebites account for 3% of all deaths in children aged 5-14 years.

Jose Louies, CEO of Wildlife Trust of India, says quacks often end up burning the bite site, cutting it open and applying various pastes on the area, all of which end up catalysing the movement of toxins in the body.

When patients are not taken to the official healthcare system, the death is not captured as a snakebite death, which leads to severe underreporting of the issue. Experts say that the actual number of people who die from snakebites in India could be several times the number reported by the government. According to the Central Bureau of Health Investigation reports (2016-20), “the average annual frequency of snakebite cases in India is around 3 lakhs and about 2,000 deaths occur due to snakebite envenoming”. This is far less than the 58,000 reported in the 2020 study.

This is where NAPSE’S proposed programme to build awareness comes in. Its primary action is to identify at-risk regions and communities, adapt WHO’s toolkit for communication and training to local contexts, organise participatory community training and engage with traditional healers, community health workers and other local leaders and activists.

It intends to persuade victims to go to medical centres, popularise first aid and support communities in adopting better healthcare-seeking behaviour.

However, there is an area where the government needs to step in: distribution of antivenoms. Louies points to issues with the distribution of antivenoms in primary health centres, particularly in the rural areas of some of the poorest regions of the country, which account for 7 out of 10 deaths from snakebites.

That this grave issue was not a priority for decades points to the inequities in the global healthcare system. While the Global North has its share of venomous snakes, their interaction with human settlements is minimal and the venom itself is less potent. On the contrary, snakebite deaths primarily happen to the poorest in the Global South.

NAPSE acknowledges this in its report: “snakebite envenoming has failed to attract requisite public health policy inclusion and investment for driving sustainable efforts to reduce the medical and societal burden. This is largely due to the demographics of the affected populations and their lack of political voice”.

It is time to change that.