It was 12:45 a.m., and October 24th had slipped into silence, its stillness stretching through forty-five minutes. My phone pulsed with messages—a river of texts, WhatsApp notes, voice messages flowing from friends and strangers alike. Amid this flurry, a single message glowed on my screen, quiet yet alive with an unexpected reverence:

Adab!

“Once, I gazed upon mountains,

Another time, wandered through the vast desert,

I sat in circles of friends, and wrestled with loneliness,

Avoided the pleading eyes of strangers on my path,

Whispered to flowers,

Sought solace in beauty’s fleeting charm…

Reading, listening to poetry…

Breathing, thinking, feeling, and penning down words…

Those words became Eighth Heaven.

Should the messenger find his way, may this Eighth Heaven come to your door.”

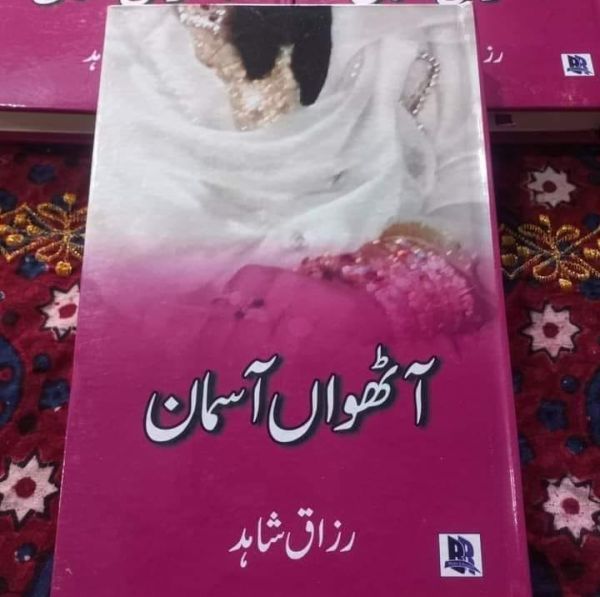

The words, tender and lyrical, carried a weight beyond their form—a whisper transformed into an invocation. They were penned by Razaq Shahid of Amrita House, Fazilpur, Rajanpur—a master of prose with the lyricism of a poet. Though we’d never met in person, his words had long been a companion. I’d spent hours lost in his writing, woven into the fabric of his world, which was both distant and familiar. If I had my way, I’d build a museum in my city, with his every sentence inscribed on the walls in careful, timeless speech bubbles. It would be a gallery of prose, eternal and public, for all to see. People would come, drawn by his words, to weave his stories into the fabric of their own lives.

On the night of October 25, 2024, I returned home from the Multan office at midnight, my body aching, my mind hollowed by the weight of work—the task of crafting hollow words into news for an industry grown numb. Waiting for me on the reading room table was a gift: Razaq Shahid’s latest book, a collection of his prose bound in reverence. I opened to the first page, and an inscription greeted me, “For your birthday, Eighth Heaven… for Amir Hussaini.” These words tugged at my heart; my eyes filled with tears, the familiar warmth of memory washing over me. I thought of my dear friend, Shamim Arif Qureshi, who once handed me his only poetry collection, Neel Kanth, inscribed with words of deep friendship. It had been a frigid winter evening. I sat in his porch, shivering despite a leather jacket. He emerged with a tray, two steaming cups of tea, and returned again with a shawl, which he draped over my shoulders. That shawl still lies in my room, a fragment of his warmth and kindness.

I read the book’s preface and laid it aside, overcome by the gravity of his words. Ghalib’s verse echoed in my mind, as if answering the silence:

“Asad’s heart continued to burn with grief,

The inferno was yet to consume the ocean.”

Today is October 26th. It is 5:00 p.m., and I step from my reading room to the gallery, cigarette in hand. The pages of Eighth Heaven unravel before me—a prose-poem painted with flashbacks, sweeping me from one frame to another. Razaq Shahid’s narrative is no simple tale but a woven canvas of lives, a kaleidoscope of voices. His story pulls us from the world of ‘Atiyya’ to the desolation of the post-partition era, through corridors of power and into the unspoken lives of history’s forgotten. In his deft prose, past, present, and future converge—a tapestry where each moment hangs, suspended and fragile, meanings barely able to hold their weight, caught in the eternal purgatory of deferred decay.

“When the one who came from Karnal planted seeds of faith in this new land, nurturing a cactus of ‘purpose,’ my grandfather left, saying, ‘Humanity will not survive here.’ Yet his brothers lingered, clinging to the narcotic of anthems. When rivers were sold, they too departed, saying, ‘This is Kufa now, and Karbala awaits us.’

When Bengal chose its path, they took me with them.

Later, I heard the parliaments speak, slicing faith for political convenience. And my grandfather, old and weary, would mutter, ‘This will fall,’ and fall it did.”

Our journey, led by Razaq’s hand, is vast, leading us to the parched desert of Thar, where a simple clerk, Khatojani, builds schools for children, holds eye camps for the blind, and buries the forgotten dead. His daily sacrifices offer a light, a resistance against the slow death of a silent nation:

“How does my house run?

Two kilos of flour from my clerk’s salary, nothing more.”

Yet, when I read his last line, “In Thar, no one shall perish for creed, nor shall blood be spilled for doctrine, as long as I live, as long as Mama Vishn breathes,” I felt my heart falter under the weight of this forgotten endurance. The memory of Dr. Shah Nawaz, the echoes of his widow’s cries, his mother’s grief, and his daughter’s pleas returned to me, haunting, as real as the silence before me.

Then, the book took me to “Jando Faqir,” where the author’s grandfather leads him on a pilgrimage to Darbar Farid. Their journey, a winding path through Bahadur Kot, becomes a corridor of memory:

“Son, the truly brave do not reside in ‘Kots’.”

The prose unfolds as a journey of layered lives, a vivid tapestry of a nation’s slow undoing—a symphony of grief, unaddressed and unclaimed. Eighth Heaven holds not only stories but lives, anchored in prose that is both narrative and monument. It is a work that captures despair yet leaves room for a glimmer of renewal, balancing on the threshold of construction and destruction.

Friends, dear readers,

One after another, I read the stories—marveling at one character’s courage, weeping at another’s tragedy, feeling the quiet reverence of their resilience. And then, I reached Journey of a Night:

“From behind the old woman, a young woman spoke:

‘Mother, how would those in cars know the hunger of those in tents? Their hunger never ends.’

And another line struck me:

“She went to lift her sleeping child from the car, but a scream pierced the air…

‘Brother, I am a mother, and I know—a sleeping child does not feel like this. I am ruined, brother!’”

At that, the cigarette fell from my fingers, and a trembling took hold of me. Tears blurred my sight, and I could go no further. This account, dear Razaq Shahid, remains unfinished.

You have shown us not an eighth heaven, but the eighth abyss—a screen stretched across the horizon where the raw agony of a forsaken earth unfolds before us. You have done this at a time when poets, writers, thinkers, and journalists have abandoned their charge, feeding on the carcass of empty words, their minds stagnant in the stench of compromised ideals. Today’s intellectuals are but a product of that mire—a legion of sycophants, none with the spirit of Har to turn toward truth at the final hour. These words may not crack open the walls of their closed minds, but I have faith the new generation will rise, that your words will become their rallying cry.

Live long, dear brother, and may you keep writing, stirring us from our slumber, from this abyss we mistake for heaven.