Nearly five years ago in Bristol, a controversial statue of Edward Colston was toppled by activists, then dumped into the city's harbour. The Grade II-listed structure of the slave trader and philanthropist was torn down on June 7, 2020, in the wake of the death of African-American George Floyd in the US.

It led to a fierce national debate about whether historic monuments with links to slavery should be removed - a lightning conductor for modern race relations.

Today, the 1895 statue of Colston, salvaged from the watery depths, has been relocated to Bristol's M Shed museum, where it is displayed in a case, lying on its side, still covered in graffiti.

Last year, the local council voted that his empty plinth should receive a new plaque explaining what happened to Colston's statue and put his role in African slavery in context. But what can the city's remaining statues tell us about Britain and its history?

I've been on a quest to visit and photograph Bristol's 20 surviving memorials to historic figures. To my delight, they revealed a remarkably diverse and stirring picture of the nation.

Surprisingly, not every trace of Edward Colston has disappeared from the city's streets. I discovered there is still an old bust of its former MP hidden away near a pair of houses in Armoury Square, St Jude's. Today it is crumbling and largely ignored by passers-by, but serves as a curious reminder of the man who sparked such controversy, 300 years after his death.

Here are some of their stories...

Samuel Morley

Samuel Morley

It's somewhat ironic that standing just a few hundred feet from Colston's empty plinth, is a statue to a noted abolitionist. Erected eight years before Colston's, it pays tribute to a former MP of the city, Samuel Morley, born in 1809.

A model employer as a woolen manufacturer, he also established a fund to finance the writings and campaigning work of Josiah Henson, an escaped American slave who also stayed with him while visiting Britain. An inscription on Morely's statue in Lewin's Mead features his quote: "I believe that the power of England is to be reckoned not by her wealth or armies, but by the purity and virtue of the great mass of her population."

Samuel PlimsollBorn in Bristol in 1824, Plimsoll deserves to be better known, for his work still saves lives today. As an MP he campaigned against what he described as "coffin ships" - vessels that put to sea overloaded and unseaworthy, which cost 500 lives a year, as many of them sank.

His idea was that each ship should bear an official mark on the hull to show how deep it should sit in the water - the safe loading limit. Against fierce opposition from vested interests, Plimsoll managed to get an act passed making the "Plimsoll Line" compulsory in 1876. The line would later inspire the name of plimsoll shoes.

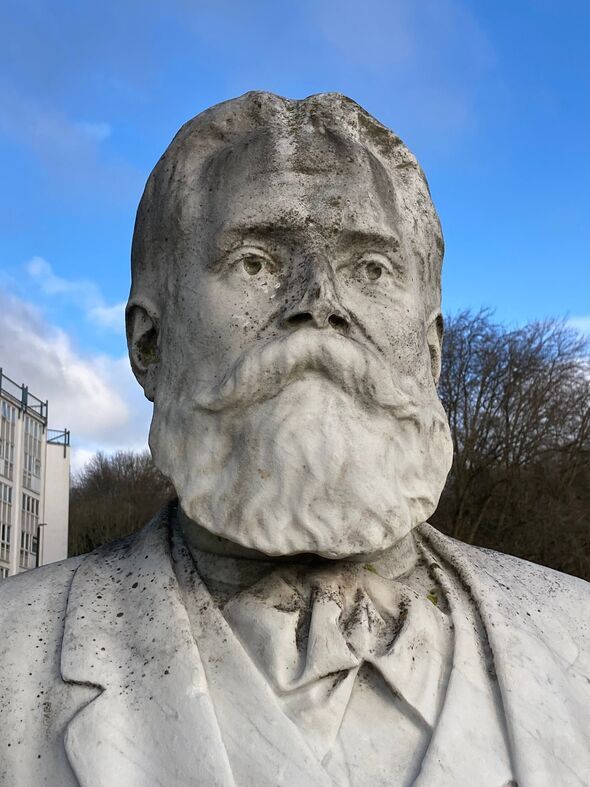

Today Plimsoll's white marble bust, at Capricorn Quay, overlooks the docks where many ships bearing his invention safely sailed off to sea.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel

On the forecourt of the grand Bristol Temple Meads station, which he designed, is a statue to Victorian engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Brunel's incredible achievements as a leader of the Industrial Revolution are synonymous with the city.

He not only built the Great Western Railway and designed the Clifton Suspension Bridge but his restored SS Great Britain, the world's first propeller-driven, ocean-going iron ship, is located there. Brunel's legacy is still everywhere across Britain today, from bridges to tunnels.

It's no wonder that, in a huge 2002 poll, he was voted second only to wartime PM Sir Winston Churchill as the 'greatest Briton'.

Alfred FagonHe was the one of first black playwrights to have his work broadcast on British television and, since 1987, a bust of the Jamaican-born writer has stood in the St Paul's area of the city, at the junction of Ashley Road and Grosvenor Road. Coming to Britain at 18, he worked for British Rail and was in the army, then became an actor.

He starred in shows like Z Cars, and wrote and produced plays in the 1970s and 1980s, while living in Bristol. Fagon, who died in 1986, broke ground with his BBC Two play Shakespeare Country about being a black actor in Britain, broadcast in 1973.

John Cabot

John Cabot

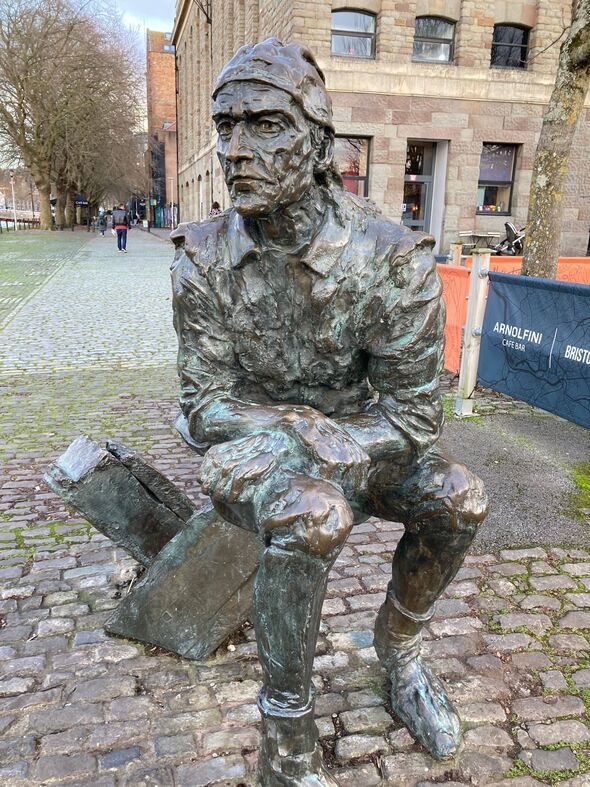

Britain has had many pioneering explorers, but a statue in Bristol's Millennium Square pays homage to an Italian-born one, who Bristol adopted as its own. He anglicized his name Giovanni Caboto, to John Cabot.

Cabot settled in the city in 1490, seeking financial support for voyages to find new routes to Asia, eventually securing the backing of local merchants and Henry VII. In 1497, with a crew of just 18, he set off in the 70ft ship Matthew, eventually arriving in a territory dunned New-found-land. Cabot actually beat Christopher Columbus to the shores of North America.

He left on another expedition in 1498, but his fate is unknown.

Edmund BurkeJust a stone's throw from Colston's former plinth, and erected the year before, is a statue to the Irish-born political thinker and Bristol MP who died in 1797. It was sporting a traffic cone when I visited - no doubt the victim of drunken students rather than protestors.

Known as the 'father of conservatism' Burke believed that a member of parliament was more than a delegate and favoured gradual change rather revolution, but did oppose the slave trade. His pedestal inscription reads: "I wish to be a member of parliament to have my share of doing good and resisting evil."

William Tyndale

William Tyndale

There are a host of statues to religious reformers in Bristol. But perhaps most notable is William Tyndale, born near the city, who also has a statue in Millennium Square.

He was an inspiration to millions of Britons by translating the Bible into English, before being burnt for heresy in the Netherlands in 1536.

Other religious figures commemorated include John Wesley, founder of the Methodist movement and campaigner for the abolition of slavery at the city's New Room, the movement's oldest preaching house. At College Green, there's a 1997 statue to Ram Mohan Roy, an Indian Hindu reformer who campaigned against child marriage and died in Bristol in 1833.

Henrietta LacksThe statue of Henrietta Lacks, erected in 2021 at the University of Bristol, was the first of a black woman, by a black woman for a UK public space. Its creator, Helen Wilson-Roe is from the city. It honours the African-American woman who died in Baltimore, aged 31, in 1951, from cervical cancer.

Some of her cells survived and multiplied and were later used in multiple scientific research projects from helping create the polio vaccine to IVF treatment.

Cary Grant

Cary Grant

Surely counting as one of Britain's finest exports, the star of films North by North West, was born humble Archie Leach into poverty in Bristol in 1904. He ran away to join the circus as a teenager and would end up in the US, where he was given a new name by studio bosses and became one of the most famous actors of his generation.

But Grant never forgot his roots. He was said to be much more English off camera than his mid-Atlantic twang suggested and he regularly returned to Bristol to see his mother, Elsie. A life-sized bronze statue was unveiled in Millennium Square by his widow Barbara Jaynes in 2001.

Queen VictoriaDominating the city's College Green is a four-ton marble statue of the monarch who reigned for 63 years. There's no doubting how much affection in which Queen Victoria has been held. This is one of 175 public monuments honouring her across the country.

Victoria embodies a period when Britain transformed politically and industrially, though to some, of course, she is the embodiment of the ills of Empire.

Another contentious figure is Earl Haig, the First World War commander, who has a statue behind the gates of Bristol's Clifton College, where he went to school. Victoria's statue, erected in 1888, seems safe in its current situation, like the ones of William III, in Queen Square and Edward VII at the Victoria Rooms.