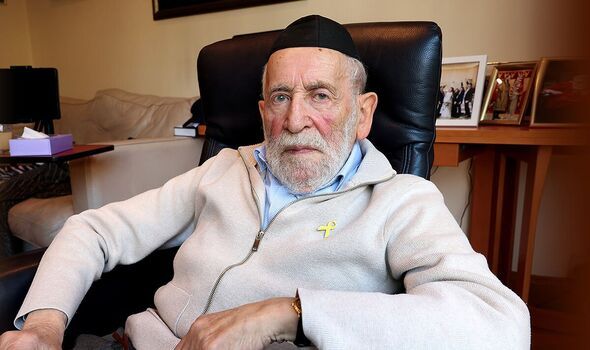

What Yisrael Abelesz chillingly calls "the first deceit" came as the cramped railway carriage in which he and his family had been travelling for three days finally came to a halt. There would be many more. "We were told to leave everything we had with us on the train, and that it will be distributed later," he recalls today at the age of 94. "Of course, it was a lie designed to create an atmosphere of calm. The Germans wanted to avoid a panic."

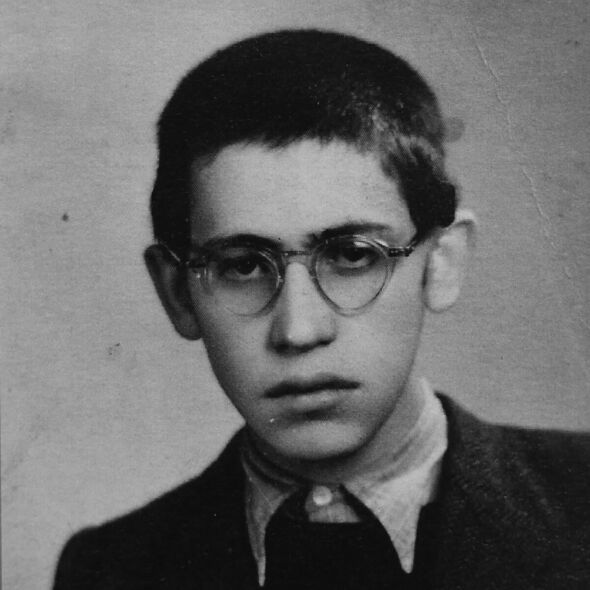

As the train carrying his family rumbled slowly west from Hungary to Poland, Yisrael, then a "precocious" schoolboy of 14 who had always kept abreast of current affairs, maintained a keen eye on the landscape as he tried to work out where they were going.

"I knew that we were somewhere near Krakow in Poland," he recalls of the journey to, and arrival at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp in July 1944. But there was no inkling that they were about to arrive at a place where families like his were forensically dismantled upon disembarkation.

"We hoped the entire family would be kept together in a camp or whatever," he sighs. "We never expected that we were arriving at the gates of hell."

This was the last time he saw his parents, David and Haya, and his younger brother, Aaron, aged just 11. "It was Sabbath, and my father didn't realise that he was about to sacrifice himself," he continues, speaking in his first-ever national newspaper interview ahead of the 80th anniversary of the camp's liberation on January 27.

As he and his older brother Binyomin, 17, disembarked the train, they were separated from the rest of their family by a man whom they later discovered was the notorious Nazi doctor, Josef Mengele, later dubbed the "angel of death" by prisoners for his cruel pseudo-science experiments.

Yisrael recalls: "Mengele asked me, 'How old are you?' I understood a bit of German, and said, 'I'm 14, it was just my birthday!'. And he said, 'That's very good, very good' and he sent me to the right side.

"I didn't know it at that time, but what he meant was, 'Very good, you can stay temporarily alive'.

"I think he was impressed that I'd had a birthday and had volunteered that."

But what Mengele gave as a birthday gift with one hand, he stole back with the other.

"My father wanted to follow me, but Mengele said, 'No, no, you go to the other side'. This was the last time I ever saw my parents and my younger brother.

"Within seconds we were moved, and they disappeared."

These harrowing memories hold ongoing power over Yisrael, who falters momentarily with emotion.

"They were all sent to the wrong side. But we didn't know then what it meant..."

However, terrible rumours were soon circulating in the barracks where he and Binyomin attempted to sleep on a concrete floor, after showering and being issued with striped blue and white uniforms.

"We asked people in the camp, 'When are we going to see our parents?' Some said, 'Later on, it will take some time before things are sorted out'. But others were cruel and said, 'Your parents are not alive anymore - you can see that smoke coming out of the chimneys, the heavy black smoke? That's where they are burning the bodies'.

"It was easy to kill with gas, but much harder to dispose of the bodies, and it was too terrible to contemplate that my parents didn't exist anymore and were up in smoke. We were a proper loving family, and everything was alright with us. The background was always love."

Yisrael's cheeks colour with emotion as he presses on.

"It was the will to tell my story to future generations that kept me alive throughout the horrors of Auschwitz," he explains.

Yisrael has given many talks about the Holocaust but has rarely spoken to the media. It's surprising when you consider he is that rarest of entities: a child survivor of Auschwitz. He is also one of fewer than 20 camp survivors living in the UK today who are known to the Holocaust Memorial Day Trust.

But now, he has invited me into his north London home to share his remarkable story of survival and courage to remind the world never to forget the Nazis' systematic murder of six million Jews during the Second World War, including the one million who perished in Auschwitz.

Yisrael was born on July 5, 1930, into an Orthodox Jewish family of comfortable means in the small Hungarian town of Kapuvar. His father David owned a wholesale grocery business and life was good for the family until the Nazis invaded Hungary in 1944 and began dismantling the rights of Jews.

The family were banished from Kapuvar before being sent to Auschwitz.

Yisrael arrived in the UK in 1949 and went on to build a successful career as a property developer alongside his wife, Judith, another survivor from Hungary, who died seven years ago, and with whom he has three daughters, Ruth, Sarah, Rachelle, and a son Moshe.

Mentioning the loss of the woman who was his emotional anchor for nearly 60 years is the only time in our interview when Yisrael's voice drops to a whisper. He then determinedly brightens, talking with pride of their children's loving care towards him.

For at the age of just 14, and with all the irrepressible vigour of youth, he was determined to survive and did so for the six months of his incarceration at Auschwitz.

"I had a very strong will. That was very important," he says. "I always wanted to have my own life in my own hands, I didn't want someone to decide for me.

"I always looked at a situation, quickly anticipated what was going to happen and acted accordingly. So, I was always running and hiding, all of the time.

"If you keep moping and worrying about your fate, it won't help you. If you are traumatised, you can't survive. So, I lived from day to day and made sure I shouldn't get caught."

The truth is that a unique blend of strategic thinking, quick-wittedness and natural charisma helped Yisrael survive for six months against all the odds in the most hellish of circumstances.

"Nobody of such a young age, of just 14-and-a-half, had survived and came back from Auschwitz. I was quite a novelty upon liberation," he admits.

And not least because he was too young for work, which Nazi guards considered a "defect" requiring permanent correction - in most cases being sent to the crematoria.

The fact that Yisrael has lived into venerable old age, and is able to tell his harrowing story, is due to a series of remarkable encounters which meant fellow members of the Jewish community, as well as hospital staff, Russian prisoners and even German soldiers took a shine to the charismatic young teenager. Each interaction provided, as it turned out, a small incremental opportunity for survival. Yisrael seized each shard of a chance, maximising his potential for survival.

On one occasion, after 25 prisoners escaped their death sentence, the numbers needed to tally and an assessment was held to pick a similar number to perish.

"I was worried the soldiers would notice me [as I was small], so I got some bricks to stand on so that I should look taller," he explains. But to his horror, he was noticed by a camp worker.

"As he pulled me out, I said to the German officer who was with him, as I flexed my non-existent muscles, 'I'm strong, I can work'. The worker told me to shut up, but the soldier said, 'Ah, leave him, leave it'. And he pushed me back and took somebody else instead of me."

On another occasion, the few surviving youngsters in the camp, including Yisrael, were rounded up and told they were going to be taken to a special children's camp with better conditions.

By now Yisrael was wise to the lies.

"I realised immediately that there was no such thing," he says.

"So, as soon as I was selected, I walked away. Nobody noticed; they were not watching because they were pretending it was going to be just an ordinary selection."

The greatest threat to Yisrael's survival, and his greatest weakness was that due to his small size he was willing to work but was never chosen. Always, I was left behind.

"My brother was tall and ready to be taken [for work], but he was left behind also because he wanted to look after me," he says.

Ten days on, and during a further selection, the Germans didn't bother to sugarcoat what was going on. "By that time, they knew that people knew what was happening, and were very strict about who was selected.

"I ran away again, but to my bad luck a German officer was watching the selection and he saw me. He sent a Jewish camp worker to fetch me who got hold of me and said in Yiddish, 'Run away from me'."

This led to a fake tussle during which Yisrael broke free and ran towards a group of Russian prisoners of war who were outside their barracks.

"I ran towards them, and they let me in and they told the officer, 'If you come in, you won't get out'. I stayed for four hours. My brother thought I had been killed."

That was the night that Yisrael knew without a doubt he was destined to live.

"I knew then that I was going to survive, because whatever was going on, it always turned out well," he recalls.

When he contracted typhoid shortly before the end of the war, a further survival epiphany occurred when he agreed to donate his blood to the Germans. Full of Typhoid antibodies, he was rewarded by the grateful men with a salami sausage. When Binyamin suggested prayers to offer should he one day be selected, Yisrael was always vehement.

"I was always shouting, saying, 'No, I don't want to die for the sanctification of God's name. I want to live for it.'"

In January 1945, against a backdrop of rumours that the war might soon be over, the camp was evacuated and Yisrael joined a so-called death march of surviving prisoners towards camps in Germany. He nearly died in the freezing cold.

"I thought then they would shoot me, but almost immediately we arrived at another camp, Althammer, and there I noticed the Germans running around like poisoned rats.

"They are always calm, so I had an instinct to hide. I just went under a bunk bed and three hours later I heard cheers."

Liberation had arrived in the form of the Russian army. Yisrael, who against all odds was eventually reunited with his surviving four siblings, eschews suggestions that people were kind to him specifically because of his youthful charm.

"Anybody who survived is a miracle because they meant to kill everybody," he says simply.

Learn more information about the Holocaust Memorial Day Trust by visiting