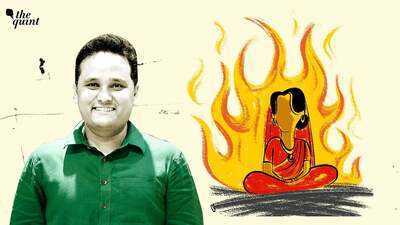

In a recent and widely viewed podcast, revisits the question of sati, a practice he deems a form of ritual suicide. He argues that the British exaggerated the incidence of widow burning in order to portray our society as barbaric. However, even as it claims to challenge colonial understandings of widow burning, Tripathi’s discussion of sati closely follows the terms of the colonial debate.

Sati is understood as a question of “tradition,” a practice that is exceptional rather than widespread and undertaken by self-determining women for “personal” reasons such as guilt.

His examples are drawn from the epics, not from the long history of documentation of the practice in other sources.

The also worked with the same binary — ritual suicide or murder. In the period before its legislative prohibition in 1829, the East India Company deputed officials to observe burnings so that they could intervene at what they considered the first sign of coercion.

In the process, the colonial bureaucracy in effect legalised sati and bestowed upon it an aura of legitimacy, provided that it was voluntary. It is likely that Amish Tripathi would not object to this, since he is not arguing against voluntary immolation.

One is prompted to ask the following questions: why the defensive indignation in 2025 when colonial representations themselves oscillated between glorifying sati and being repulsed by it?

We may grant that colonial officials were concerned about intervening in what they narrowly, at times ambivalently, construed as “tradition” in order to protect their economic and political interests. We may also agree that the practice served missionaries in arguing for conversion.

But 78 years after Independence, why is sati still being debated primarily as a question of “tradition?” Why is it not considered a question of the inherent value of women’s lives? Why is it not being discussed as a practice of violent cruelty?

In my book Contentious Traditions: The Debate on Sati in Colonial India, I argued that, contrary to the way it has been represented, the debate on sati was at its core a debate about tradition.

The women who were burned were marginal to it; the controversy was primarily over how Hindu tradition was to be understood by an occupying state seeking to consolidate its authority, a fact that trumped its so-called civilising mission.

Women were simply the ground of the debate — they were neither subjects nor even objects. This is also true in the current instance and reinforced by Amish Tripathi's reliance on epics rather than on historical evidence.

Reframing the Debate: Women, Not Just TraditionRegrettably, it is still all too common to evaluate violence, life, and death in terms other than the flesh and blood of the humans involved.

Discussion of women’s rights frequently proceed as if the issue were primarily a contest over men’s prerogatives.

In a similar vein, the rights of minorities are often debated as if they were more properly about, and thus subordinate to, the lives of the majority.

To all those who extol a woman’s self-immolation at the death of her husband, one wishes to ask if they can imagine helping their own mother or sister onto a funeral pyre. No doubt there will be those who insist that they can.

But for the rest, perhaps such an exercise might serve to redirect the focus from abstract disquisitions on sati or tradition — untouched by the fire of death — to women in all their vibrant aliveness.

(Lata Mani is a historian, cultural critic, and author of books such as Contentious Traditions: The Debate on Sati in Colonial India (1998) and Sacred Secular: Contemplative Cultural Critique (2009). This is an opinion piece. The views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)