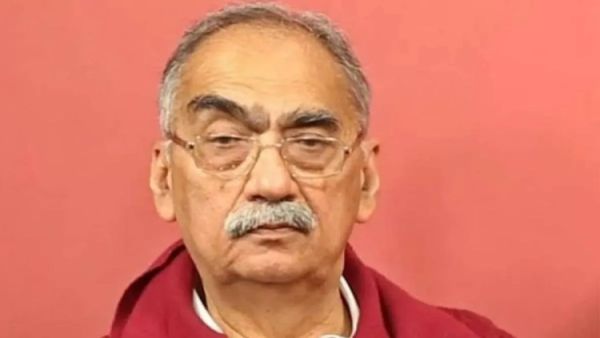

Vivek Katju The interests of nations form the foundation of international relations. Countries must modify their policies and actions to further their interests as the world situation evolves.

As a result, it is stated that nations have merely everlasting interests rather than everlasting friends or foes. Over the last several years, India has had to confront these fundamental realities in both its commercial and economic spheres as well as in relation to its security.

Although President Donald Trump has often claimed that Prime Minister Modi is his buddy, his statement that “Dosti hai, lekin dhanda toh dhanda hai” is shown by his decision to increase tariffs on India as part of his policy to do so against almost every other nation. Furthermore, when China attempted to use force to alter the status quo in Eastern Ladakh in 2020, it violated all agreements pertaining to the administration of the Line of Actual Control, even though Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping had a personal understanding.

India’s present national attention and energy should be dedicated solely to solving the security issues and the changing international environment in the domains of business and trade. Social cohesion must be preserved for this reason.

Therefore, none of India’s political parties or forces should adopt any actions that might jeopardize interfaith peace or relationships. The country’s interests may be harmed by the present tendency by some political factions to define the medieval era of this nation’s history as one of slavery. Therefore, any discussion of India having been enslaved for a thousand years must be avoided.

It is true that many temples were destroyed by medieval invaders, and it is normal for many Hindu groups to feel offended and furious when they witness ancient idols that have intentional damage or the remains of temples that have been assaulted. As a Hindu, I too experience anger, but I feel obligated to prioritize India’s interests above all other considerations. That makes me focus on the here and now rather than the past.

The Indian Freedom Movement’s leaders prioritized India’s desire to maintain the British political and administrative structure after its independence. They did not care that they had been persecuted and imprisoned by the British.

One of the greatest leaders of India’s national movement, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, agreed that individuals who had worked with the British by serving in the British Indian army, police, bureaucracy, and judiciary would remain in their positions for the sake of India’s security. In fact, he was adamantly opposed to the idea that the British form of government should not be applied to free India.

In an unpublished autobiography, my grandfather Kailas Nath Katju quotes Sardar Patel as stating that India has been married to British political ideologies for the last 150 years, from the start of British control in the country. As a result, any changes to the Parliamentary political system were rejected by the great Sardar. For India’s needs once independent, he also disregarded the horrors of British colonialism, including the murder at Jallianwala Bagh. He and the other leaders likely never forgot or forgave British colonial exploitation, but they set it aside for the sake of India.

Regarding the medieval era of Indian history, the same mindset must be used. Even if there have been significant historical wrongs, national unity is required to meet today’s strategic and developmental needs, not to revisit old wounds. It is also true that throughout the Middle Ages, when Muslims ruled India, certain individuals or groups fought it while others worked with it. Others who weren’t Muslims converted to Islam.

Focusing on all of this gets quite contentious. One member of Parliament’s comments on the legendary hero Rana Sanga recently caused such a storm. Even within Hindus, societal cohesion may be undermined by the reopening of roles performed by various individuals or groups.

As an example, consider how various factions reacted to Sadashiv Rao Bhao’s Peshwa soldiers when they fought the Afghan invader Ahmed Shah Abdali both before and during the third battle of Panipat in 1761. If they are given attention today, they would simply result in needless disputes that will separate Hindus rather than bring them together as certain political, cultural, and social groupings would want.

Modi recently used language in his podcast with Lex Fridman that suggests he views the Mughals as colonialists on par with the British and other European countries. There is a risk involved. It is a truth that certain non-Islamic organizations allied themselves with the Mughals, much as many Indians worked with the British.

They rose to top administrative positions and became their generals. Some formed marriage partnerships with them. How should we see the individuals and organizations that worked with the Mughals, even if we naturally and rightly regard Shivaji and Maharana Pratap as great heroes? Political forms should concentrate on India’s medieval past because their ancestors are still living. This does not imply that the Indian government should refrain from implementing reforms in the practices of all segments of the Indian population.

As seen in other faiths, Hindu civilization had numerous social ills, but centuries ago it had closed its doors to schisms. In several of his articles in this publication, the author has emphasized the need for continuing social reform initiatives so that Hindu society, as a subset of Indian society as a whole, might achieve true equality both in theory and in reality.

The Indian political and cultural leadership should be aware that the doors to schisms that are closed should never be opened, even while all attempts to eradicate ideas of higher and lower status among Hindus must continue vigorously. For this reason, Hindus and India as a whole must maintain a tolerant stance toward diversity.