Are we in danger of losing our tiger reserves — the last vestiges of pristine forests left in India? So it would seem. The Modi government has green signalled mining, roads and now the bifurcation of tiger reserves created specifically to protect forested areas from so-called ‘development’ projects. With decisions that go against our forest conservation and wildlife protection laws, the government has once again made a complete mockery of our institutions.

India’s most impressive achievement in tiger conservation has been to successfully maintain tiger populations within their natural geographical distribution. With most of our tiger reserves and sanctuaries being subsumed by linear projects (railway lines, canals, roads, airports) that end up fragmenting our forests, our wildlife cannot move freely.

Both Rajasthan’s Sariska Tiger Reserve and the Panna Tiger Reserve in Madhya Pradesh had lost their tiger populations to poaching. In 2010, then Union environment minister Jairam Ramesh had five tigers relocated from Ranthambore to Sariska to rebuild the population. Even as the tiger population stabilised, illegal mining continued in and around Sariska.

The reasons are obvious. Situated in the Aravalli mountain range, the reserve is rich in mineral resources — marble, limestone, dolomite, masonic stone. Mining is the second most important source of revenue for Rajasthan — illegal mining in and around Sariska generated nearly two crore rupees of revenue per day. Both the Union and state ministers of environment, forests and climate change — Bhupender Yadav and Sanjay Sharma respectively — are from Alwar. According to local activists, both have close connections with the mining lobby.

No surprise, therefore, that the Union environment minister has proposed redrawing the reserve’s boundaries, cutting around 50 sq. km of mineral-rich, hilly terrain in Tehla tehsil — an area critical to tiger conservation — and replacing it with 91 sq. km of less sensitive land from the surrounding buffer zone.

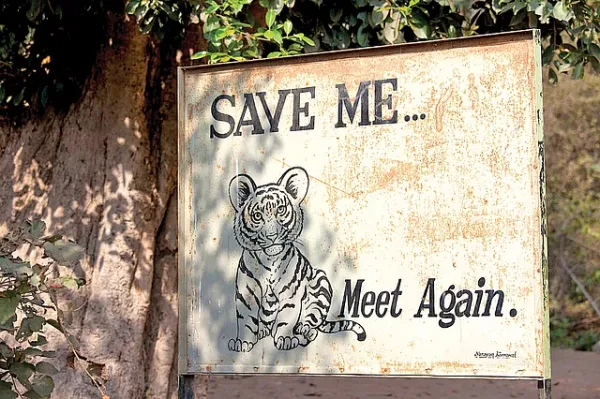

Sariska: Will its tigers be mined into oblivion by a human predator — again?

Sariska: Will its tigers be mined into oblivion by a human predator — again?

This ‘rationalisation’ of boundaries will reactivate the 47 mines located within a kilometre of Sariska — which the Supreme Court had closed down in May 2024 — bringing them back into the buffer zone. Local foresters warn that excluding Tehla tehsil’s peripheral hills would cut off internal corridors vital to the tigers’ movement.

Debadityo Sinha, the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy’s lead on climate and ecosystems, points out that these tiger reserves “have been set up to prioritise wildlife conservation over other development activities. Mining activities result in increased human presence, noise and pollution caused by dust and increased transportation, the destruction of aquifers and the complete erosion of the sanctity of these places”.

Sariska is not the only tiger reserve whose boundary is being redrawn. A ‘holistic plan’ has been developed by the Wildlife Institute of India whereby a 10 km radius around the Rajaji Tiger Reserve has been redrawn to protect wildlife corridors and to address mining and resource extraction activities.

After liquor, mining remains Uttarakhand’s main source of income. A first in the country — indeed the world — is the construction of a boundary wall near the Lansdowne Forest Division (part of the Rajaji Tiger Reserve) to mitigate human–wildlife conflict. Hasn’t anyone realised that elephants, tigers and leopards are not cowed by walls?

“Building a wall around a tiger reserve on which hundreds of crores have been spent is unheard of. But permitting mining around the tiger reserve, knowing full well it will affect animal movement, is horrific,” said environmentalist Reena Paul.

Illegal mining near Sariska Tiger Reserve: SC tells Rajasthan to appoint nodal officerRajeev Mehta, honorary member of the Uttarakhand wildlife board, pointed out, “I recently attended the state wildlife board meeting chaired by chief minister Pushkar Singh Dhami. Instead of discussing the incessant road building in Rajaji Tiger Reserve or focusing on why additional land is being taken from this reserve to extend the Jolly Grant Airport, the chief minister focused on two issues: the immediate need to double the quantity of boulders being taken out of the rivers, and convert the single lane cutting through the reserve to a Shiva temple near Rishikesh to a four-lane road! Why? So that more pilgrims can visit, never mind the disturbance to the wildlife.”

The most criminal of all actions was the inauguration of the Ken–Betwa river interlinking project, which will end up submerging 80 per cent of the Panna Tiger Reserve — wiping out habitat crucial for the survival of tigers and other species. The project also entails the felling of over 23 lakh trees, effectively destroying an entire ecosystem.

The tiger population at Panna had been wiped out by 2009. Here too, on the initiative of Jairam Ramesh, tigers were reintroduced. Dr Raghu Chundawat, scientist and wildlife activist, a resident of Panna since 1995, calls the Rs 45,000 crore Ken–Betwa interlinking project a “poorly conceived” one, bound to cost us dearly.

“The government claims the Ken river has surplus water while the Betwa river has less, hence water should be diverted from one to the other. This is a complete lie. Their calculations are based on river flow data that’s 40 years old and no longer valid. Yet, they’ve refused to release it in the public domain, on the excuse that ‘international water data’ cannot be shared as both rivers flow into the Ganga, which in turn flows into the Padma in Bangladesh,” said Chundawat.

“The truth is, the Panna region grows crops like wheat and chickpeas, which need less water, while the Betwa region grows water-intensive crops like sugarcane. Ninety per cent of Madhya Pradesh is water-stretched because of over-utilisation. At this rate, I fear the entire state will end up becoming water scarce,” he added.

Seven dams have already been built downstream on the Betwa river. With new dams planned upstream, the existing structures may no longer be able to supply water to Uttar Pradesh. The government’s solution is to divert water from Ken to Betwa. But they are overlooking a critical issue — the Ken is no longer a perennial river, as its flow has dropped drastically. Water experts are now asking a crucial question: where will the additional water come from to support such a massive interlinking project?

Another destructive move is the Uttarakhand state government’s determination to construct the Kandi road from Kotdwar to Ramnagar, which will split Corbett National Park. Former state forest minister Harak Singh Rawat had even petitioned the Centre, insisting that the construction of this road was a ‘defence requirement’. Although the Supreme Court shot it down, there’s talk that the government wants to revive it in order to please vote banks and the all-powerful contractor lobbies.