A study conducted on a near-Earth asteroid could call into question details we thought we knew about how our planet's oceans came to be, researchers have said. The team of experts, based in Japan, have found that the parent asteroid of Ryugu retained water in ice form for billions of years - far longer than initially estimated.

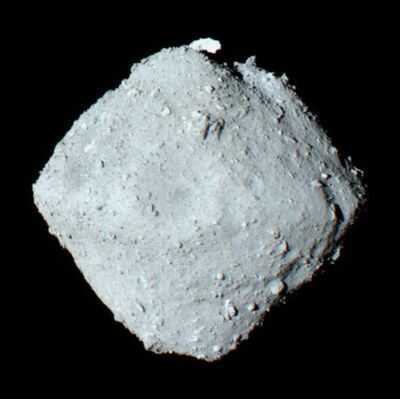

The Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency's Hayabusa2 spacecraft collected samples from Ryugu - a 3,000ft in diameter asteroid first discovered in 1999 - which were analysed by a team of researchers led by Tsuyoshi Iizuka, associate professor of cosmochemistry at the University of Tokyo. The discovery of this ancient ice appears to suggest that asteroids delivered ice to Earth as well as water, in the form of hydrous minerals (minerals that contain chemically bound water within their crystal structure). "This changes how we think about the long-term fate of water in asteroids," said Prof Iizuka, according to Discover.

Approximately 5.56 billion years ago, asteroids are estimated to have formed on the outskirts of our solar system and were full of carbon and water. Rather than water reacting to form hydrous minerals or simply evaporating, instead, in the form of Ryugu's parent body, it retained the water in the form of ice for over a billion years.

Researchers believe that through isotope dating of the samples, there was some kind of collision with another celestial object, at which point the ice melted and evaporated. Crashes like this distorted the sample's age, at first making it appear that they were older than the solar system, estimated to be 4.8 billion years old.

Previously, experts thought that carbonaceous asteroids - integral components for Earth - were responsible for carrying several oceans' worth of water inside minerals. However, with the discovery of this ancient ice, researchers now reckon the asteroids may have delivered two to three times more water than previously thought - equivalent to 60 to 90 times the mass of Earth's oceans combined.

According to isotope comparisons, approximately 6% of Earth's matter is made up of material from asteroids like Ryugu. Therefore, the total water delivered to Earth could have been up to 1.8% of the planet's mass.

"We found that Ryugu preserved a pristine record of water activity, evidence that fluids moved through its rocks far later than we expected," said Prof Iizuka, one of the author of the study published by Nature. "The water hung around for a long time and was not exhausted so quickly as thought."

"The idea that Ryugu-like objects held on to ice for so long is remarkable," he added. "It suggests that the building blocks of Earth were far wetter than we imagined. This forces us to rethink the starting conditions for our planet's water system."

Researchers are now looking to discover where this water has gone since. Prof Iizuka and his team plan to investigate the amount of water that escaped into space when Earth was being formed and how much remained in the planet's core and on its surface to produce Earth's environment as we know it today.

"Though it's too early to say for sure, my team and others might build on this research to clarify things, including how and when our Earth became habitable," he said.